fossil fuels

With the failure of a global plastics treaty—oil-rich nations and the petrochemical industry putting up the strongest opposition—the following article should give food for thought, especially as every mouthful of seafood contains microplastics.

We’ve all seen the impact of our plastic addiction. It’s hard to miss the devastating images of whales and sea birds that have died with their stomachs full of solidified fossil fuels. The recent discovery of a plastic bag in the Mariana Trench, at over 10,000 metres below sea level, reminds us of the depth of our problem. Now, the breadth is increasing too. New research suggests that chemicals leaching from the bags and bottles that pepper our seas are harming tiny marine organisms that are central to sustained human existence.

Once plastic waste is out in the open, waves, wind and sunlight cause it to break down into smaller pieces. This fragmentation process releases chemical additives, originally added to imbue useful qualities such as rigidity, flexibility, resistance to flames or bacteria, or a simple splash of colour. Research has shown that the presence of these chemicals in fresh water and drinking water can have grave effects, ranging from reduced reproduction rates and egg hatching in fish, to hormone imbalances, reduced fertility or infertility, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer in humans.

But very little research has looked at how these additives might affect life in our oceans. To find out, researchers at Macquarie University prepared seawater contaminated with differing concentrations of chemicals leached from plastic bags and PVC, two of the most common plastics in the world. They then measured how living in such water affected the most abundant photosynthesising organism on Earth – Prochlorococcus. As well as being a critical foundation of the oceanic food chain, they produce 10% of the world’s oxygen.

The results indicate that the scale and potential impacts of plastic pollution may be far greater than most of us had imagined. They showed that the chemical-contaminated seawater severely reduced the bacteria’s rate of growth and oxygen production. In most cases, bacteria populations actually declined.

What can be done?

Given the importance of oxygen levels to the rate of global heating, and the vital role these phytoplankton play in ensuring thriving marine ecosystems, it is essential that we now conduct research outside of the laboratory into the effects of plastic additives on bacteria in the open seas. In the meantime, we need to take active steps to reduce the risks of chemical plastic pollution.

The clear first step is to reduce the amount of plastic entering the ocean. Recent EU and UK bans on single-use plastics are a start, but much more radical policies are needed now to reduce the role plastic plays in our lives as well as to stop the plastic we do use being released into waterways and dramatically improve appallingly low recycling rates.

At an international level, we must make addressing the waste produced by the fishing industry a priority. Broken fishing nets alone account for almost half of the plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch – and lost or discarded fishing gear accounts for one-third of the plastic litter in European seas. EU incentives announced in 2019 to tackle this waste do not go far enough.

Legislation is also urgently needed to limit the industrial use of harmful chemical additives to a level that is absolutely necessary. As an example, bisphenol A, found in myriad products ranging from receipt paper to rubber ducks, is now listed as a “substance of very high concern” due to its hormone-disrupting effects. But as yet the few existing laws regulating the chemical do not cover the majority of industrial use. This needs to change – as quickly as possible.

Of course, even if we can completely stop new chemicals from reaching the oceans, we will still have a legacy of plastic and associated chemical pollution to deal with. At the moment, we have no idea whether we’ve already done irreversible damage, or if marine ecosystems are resilient to current levels of plastic pollution in the open oceans. But the health of our oceans is not something we can risk. So, in addition to physical removal schemes such as The Ocean Clean Up, we need to invest in chemical removal technologies as well.

In salty ocean environments, such technologies are under-researched. We are currently in the early stages of developing a floating device that uses a small electric circuit to transform BPA into easily retrievable solid matter, but our work alone is not enough. Scientists and governments need to ramp up their efforts to both understand and eliminate the problem of chemical contamination of our oceans, before it’s too late.

While ocean bacteria may seem far removed from our daily lives, we are dependent on these tiny organisms to maintain the balance of our ecosystems. We ignore their plight at our peril.![]()

Kate Dooley, Senior Research Fellow, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

____________________________________________________________________________

Negotiators at the COP29 climate conference in Baku have struck a landmark agreement on rules governing the global trade of carbon credits, bringing to a close almost a decade of debate over the controversial scheme.

The deal paves the way for a system in which countries or companies buy credits for removing or reducing greenhouse gas emissions elsewhere in the world, then count the reductions as part of their own climate efforts.

Some have argued the agreement provides crucial certainty to countries and companies trying to reach net-zero through carbon trading, and will harness billions of dollars for environmental projects.

However, the rules contain several serious flaws that years of debate have failed to fix. It means the system may essentially give countries and companies permissions to keep polluting.

What is carbon offsetting?

Carbon trading is a system where countries, companies or other entities buy or sell “credits”, or permits, that allow the buyer to offset the greenhouse gas emissions they produce.

For example, an energy company in Australia that produces carbon emissions by burning coal may, in theory, offset their impact by buying credits from a company in Indonesia that removes carbon by planting trees.

Other carbon removal activities include renewable energy projects, and projects that retain vegetation rather than cutting it down.

Carbon trading was a controversial part of the global Paris climate deal clinched in 2015.

The relevant part of the deal is known as “Article 6”. It sets the rules for a global carbon market, supervised by the United Nations, which would be open to companies as well as countries. Article 6 also includes trade of carbon credits directly between countries, which has begun operating even while rules were still being finalised.

Rules for carbon trading are notoriously complex and difficult to negotiate. But they are important to ensure a scheme reduces greenhouse gas emissions in reality, not just on paper.

A long history of debate

Over the past few years, annual COP meetings made some progress on advancing the carbon trading rules.

For example, COP26 in Glasgow, held in 2021, established an independent supervisory body. It was also tasked with other responsibilities such as recommending standards for carbon removal and methods to guide the issuing, reporting and monitoring of carbon credits.

But the recommendations were rejected at COP meetings in 2022 and 2023 because many countries viewed them as weak and lacking a scientific basis.

At a meeting in October this year, the supervisory body published its recommendations as “internal standards” and so bypassed the COP approval process.

At this year’s COP in Baku, the Azerbaijani hosts rushed through adoption of the standards on day one, prompting claims proper process had not been followed

For the remaining two weeks of the conference, negotiators worked to further develop the rules. A final decision was adopted over the weekend, but has attracted criticism.

For example, the Climate Land Ambition and Rights Alliance says the rules risk “double counting” – which means two carbon credits are issued for only one unit of emissions reduction. It also claims the rules fail to prevent harm to communities – which can occur when, say, Indigenous Peoples are prevented from accessing land where tree-planting or other carbon-storage projects are occurring.

Getting to grips with carbon removal

The new agreement, known formally as the Paris Agreement Trading Mechanism, is fraught with other problems. Most obvious is the detail around carbon removals.

Take, for example, the earlier scenario of a coal-burning company in Australia offsetting emissions by buying credits from a tree-planting company in Indonesia. For the climate to benefit, the carbon stored in the trees should remain there as long as the emissions produced from the company’s burning of coal remains in the atmosphere.

But, carbon storage in soils and forests is considered temporary. To be considered permanent, carbon must be stored geologically (injected into underground rock formations).

The final rules agreed to at Baku, however, fail to stipulate the time periods or minimum standards for “durable” carbon storage.

Temporary carbon removal into land and forests should not be used to offset fossil fuel emissions, which stay in the atmosphere for millennia. Yet governments are already over-relying on such methods to achieve their Paris commitments. The weak new rules only exacerbate this problem.

To make matters worse, in 2023, almost no carbon was absorbed by Earth’s forests or soils, because the warming climate increased the intensity of drought and wildfires.

This trend raises questions about schemes that depend on these natural systems to capture and store carbon.

What next?

Countries already can, and do, trade carbon credits under the Paris Agreement. Centralised trading will occur under the new scheme once the United Nations sets up a registry, expected next year.

Under the new scheme, Australia should rule out buying credits for land-based offsets (such as in forests and soil) to compensate for long-lasting emissions from the energy and industry sectors.

Australia should also revise its national carbon trading scheme along the same lines.

We could also set a precedent by establishing a framework that treats carbon removals as a complement — not a substitute — for emissions reduction.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The world is striving to reach net-zero emissions as we try to ward off dangerous global warming. But will getting to net-zero actually avert climate instability, as many assume?

Our new study examined that question. Alarmingly, we found reaching net-zero in the next few decades will not bring an immediate end to the global heating problem. Earth’s climate will change for many centuries to come.

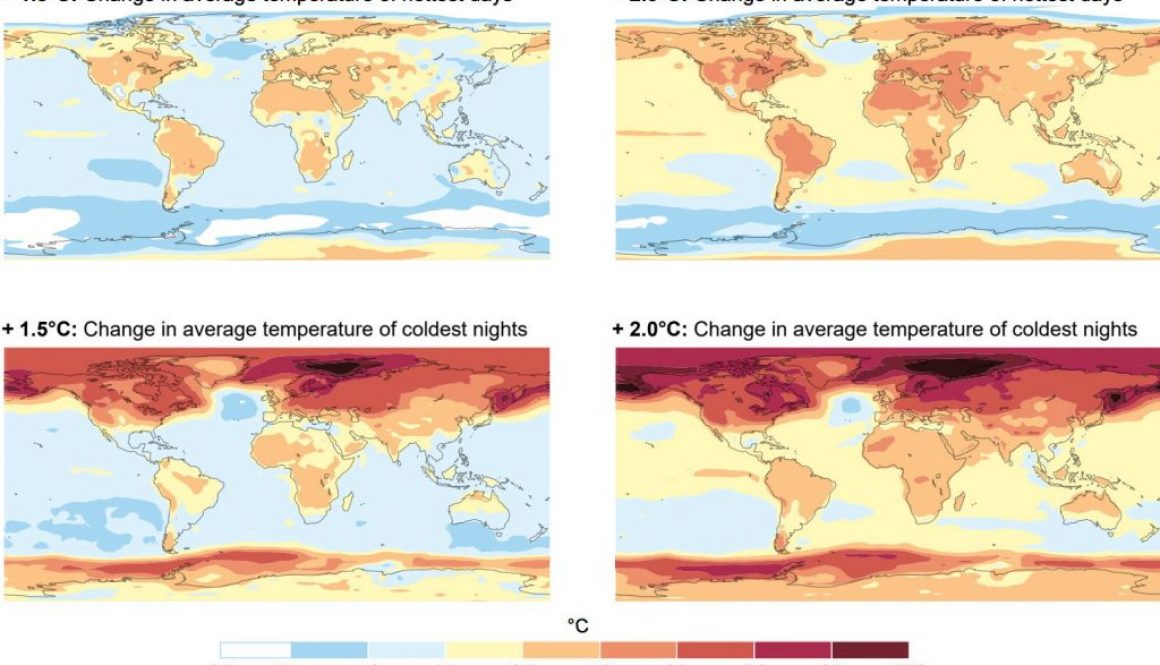

And this continuing climate change will not be evenly spread. Australia would keep warming more than almost any other land area. For example if net-zero emissions are reached by 2060, the Australian city of Melbourne is still predicted to warm by 1°C after that point.

But that’s not to say the world shouldn’t push to reach net-zero emissions as quickly as possible. The sooner we get there, the less damaging change the planet will experience in the long run.

Reaching net-zero is vital

Global greenhouse gas emissions hit record highs in 2023. At the same time, Earth experienced its hottest year.

Analysis suggests emissions may peak in the next couple of years then start to fall. But as long as emissions remain substantial, the planet will keep warming.

Most of the world’s nations, including Australia, have signed up to the Paris climate agreement. The deal aims to keep global warming well below 2°C, and requires major emitters to reach net-zero as soon as possible. Australia, along with many other nations, is aiming to reach the goal by 2050.

Getting to net-zero essentially means nations must reduce human-caused greenhouse gas emissions as much as possible, and compensate for remaining emissions by removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere elsewhere. Methods for doing this include planting additional vegetation to draw down and store carbon, or using technology to suck carbon out of the air.

Getting to net-zero is widely considered the point at which global warming will stop. But is that assumption correct? And does it mean warming would stop everywhere across the planet? Our research sought to find out.

Centuries of change

Computer models simulating Earth’s climate under different scenarios are an important tool for climate scientists. Our research used a model known as the Australian Community Climate and Earth System Simulator.

Such models are like lab experiments for climate scientists to test ideas. Models are fed with information about greenhouse gas emissions. They then use equations to predict how those emissions would affect the movement of air and the ocean, and the transfer of carbon and heat, across Earth over time.

We wanted to see what would happen once the world hit net-zero carbon dioxide at various points in time, and maintained it for 1,000 years.

We ran seven simulations from different start points in the 21st century, at five-year increments from 2030 to 2060. These staggered simulations allowed us to measure the effect of various delays in reaching net-zero.

We found Earth’s climate would continue to evolve under all simulations, even if net-zero emissions was maintained for 1,000 years. But importantly, the later net-zero is reached, the larger the climate changes Earth would experience.

Warming oceans and melting ice

Earth’s average temperature across land and sea is the main indicator of climate change. So we looked at that first.

We found this temperature would continue to rise slowly under net-zero emissions – albeit at a much slower rate than we see today. Most warming would take place on the ocean surface; average temperature on land would only change a little.

We also looked at temperatures below the ocean surface. There, the ocean would warm strongly even under net-zero emissions – and this continues for many centuries. This is because seawater absorbs a lot of energy before warming up, which means some ocean warming is inevitable even after emissions fall.

Over the last few decades of high greenhouse gas emissions, sea ice extent fell in the Arctic – and more recently, around Antarctica. Under net-zero emissions, we anticipate Arctic sea ice extent would stabilise but not recover.

In contrast, Antarctic sea ice extent is projected to fall under net-zero emissions for many centuries. This is associated with continued slow warming of the Southern Ocean around Antarctica.

Importantly, we found long-term impacts on the climate worsen the later we reach net-zero emissions. Even just a five-year delay would affect on the projected climate 1,000 years later.

Delaying net-zero by five years results in a higher global average surface temperature, a much warmer ocean and reduced sea ice extent for many centuries.

Australia’s evolving climate

The effect on the climate of reaching net-zero emissions differs across the world.

For example, Australia is close to the Southern Ocean, which is projected to continue warming for many centuries even under net-zero emissions. This warming to Australia’s south means even under a net-zero emissions pathway, we expect the continent to continue to warm more than almost all other land areas on Earth.

For example, the models predict Melbourne would experience 1°C of warming over centuries if net-zero was reached in 2060.

Net-zero would also lead to changes in rainfall in Australia. Winter rainfall across the continent would increase – a trend in contrast to drying currently underway in parts of Australia, particularly in the southwest and southeast.

Knowns and unknowns

There is much more to discover about how the climate might behave under net-zero.

But our analysis provides some clues about what climate changes to expect if humanity struggles to achieve large-scale “net-negative” emissions – that is, removing carbon from the atmosphere at a greater rate than it is emitted.

Experiments with more models will help improve scientists’ understanding of climate change beyond net-zero emissions. These simulations may include scenarios in which carbon removal methods are so successful, Earth actually cools and some climate changes are reversed.

Despite the unknowns, one thing is very clear: there is a pressing need to push for net-zero emissions as fast as possible.

The COP28 climate summit in Dubai has adjourned. The result is “The UAE consensus” on fossil fuels.

This text, agreed upon by delegates from nearly 200 countries, calls for the world to move “away from fossil fuels in energy systems in a just, orderly and equitable manner”. Stronger demands to “phase out” fossil fuels were ultimately unsuccessful.

The agreement also acknowledges the need to phase down “unabated” coal burning and transition towards energy systems consistent with net zero emissions by 2050, while accelerating action in “the critical decade” of the 2020s.

As engineers and scientists who research the necessary changes to pull off this energy system transition, we believe this agreement falls short in addressing the use of fossil fuels at the heart of the climate crisis.

Such an approach is inconsistent with the scientific consensus on the urgency of drastically reducing fossil fuel consumption to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

‘Abated’ v ‘unabated’

The combustion of coal, oil and gas accounts for 75% of all global warming to date – and 90% of CO₂ emissions.

So what does the text actually ask countries to do with these fuels – and what loopholes might they exploit to continue using them well into the future?

Those countries advocating for the ongoing use of fossil fuels made every effort to add the term “unabated” whenever a fossil fuel phase-down or phase-out was proposed during negotiations.

“Abatement” in this context typically means using capture capture and storage technology to stop CO₂ emissions from engines and furnaces reaching the atmosphere.

However, there is no clear definition of what abatement would entail in the text. This ambiguity allows for a broad and and easily abused interpretation of what constitutes “abated” fossil fuel use.

Will capturing 30% or 60% of CO₂ emissions from burning a quantity of coal, oil or gas be sufficient? Or will fossil fuel use only be considered “abated” if 90% or more of these emissions are captured and stored permanently along with low leakage of “fugitive” emissions of the potent greenhouse gas methane, which can escape from oil and gas infrastructure?

This is important. Despite the agreement supposedly honouring “the science” on climate change, low capture rates with high residual and fugitive emissions are inconsistent with what research has shown is necessary to limit global warming to the internationally agreed guardrails of 1.5°C and 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures.

In a 2022 report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicated that almost all coal emissions and 33%-66% of natural gas emissions must be captured to be compatible with the 2015 Paris agreement.

That’s assuming that the world will have substantial means of sucking carbon (at least several billion tonnes a year) from the air in future decades. If these miracle machines fail to materialise, our research indicates that carbon capture would need to be near total on all fuels.

The fact that the distinction between “abated” and “unabated” fossil fuels has not been clarified is a missed opportunity to ensure the effectiveness of the Dubai agreement. This lack of clarity can prolong fossil fuel dependence under the guise of “abated” usage.

This would cause wider harm to the transition by allowing continued investment in fossil fuel infrastructure – new coal plants, for instance, as long as some of the carbon they emit is captured (abated) – thereby diverting resources from more sustainable power sources. This could hobble COP28’s other goal: to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030.

By not explicitly defining these terms, COP28 missed the chance to set a firm, scientifically-backed benchmark for future fossil fuel use.

The coming age of carbon dioxide removal

Since the world is increasingly likely to overshoot the temperature goals of the Paris agreement, we must actively remove more CO₂ from the atmosphere – with reforestation and direct air capture (DAC), among other methods – than is emitted in future.

Some carbon removal technologies, such as DAC, are very early in their development and scaling them up to remove the necessary quantity of CO₂ will be difficult. And this effort should not detract from the urgent need to reduce emissions in the first place. This balanced approach is vital to not only halt but reverse the trajectory of warming, aligning with the ambitious goals of the Paris agreement.

There has only really been one unambiguously successful UN climate summit: Paris 2015, when negotiations for a top-down agreement were ended and the era of collectively and voluntarily raising emissions cuts began.

A common commitment to “phase down and then out” clearly defined unabated fossil fuels was not reached at COP28, but it came close with many parties strongly in favour of it. It would not be surprising if coalitions of like-minded governments proceed with climate clubs to implement it.

By: Professor of Energy and Climate Change, University of Manchester. Republished in full from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. See the original article: March 25, 2023

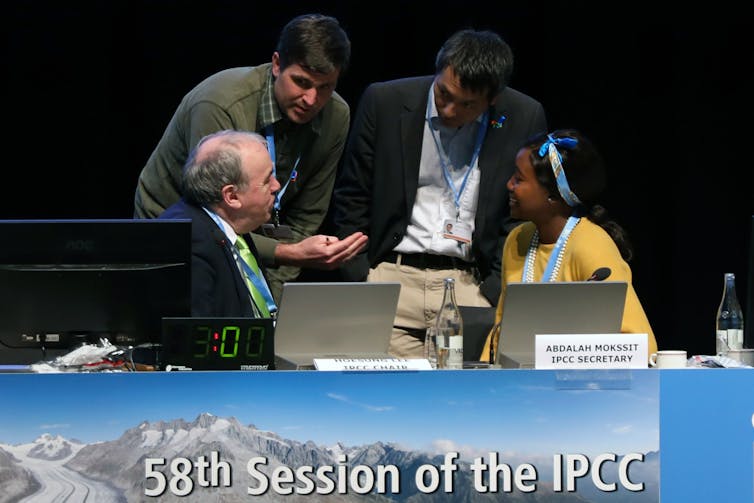

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) synthesis report recently landed with an authoritative thump, giving voice to hundreds of scientists endeavouring to understand the unfolding calamity of global heating. What’s changed since the last one in 2014? Well, we’ve dumped an additional third of a trillion tonnes of CO₂ into the atmosphere, primarily from burning fossil fuels. While world leaders promised to cut global emissions, they have presided over a 5% rise.

The new report evokes a mild sense of urgency, calling on governments to mobilise finance to accelerate the uptake of green technology. But its conclusions are far removed from a direct interpretation of the IPCC’s own carbon budgets (the total amount of CO₂ scientists estimate can be put into the atmosphere for a given temperature rise).

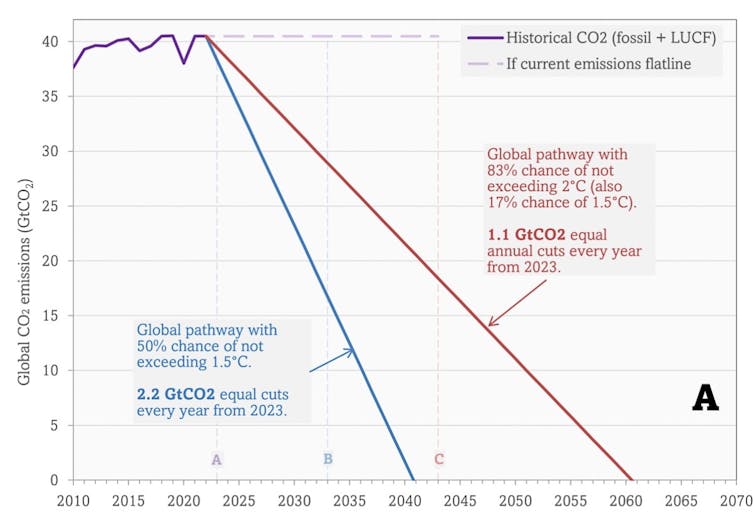

The report claims that, to maintain a 50:50 chance of warming not exceeding 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, CO₂ emissions must be cut to “net-zero” by the “early 2050s”. Yet, updating the IPCC’s estimate of the 1.5°C carbon budget, from 2020 to 2023, and then drawing a straight line down from today’s total emissions to the point where all carbon emissions must cease, and without exceeding this budget, gives a zero CO₂ date of 2040.

Given it will take a few years to organise the necessary political structures and technical deployment, the date for eliminating all CO₂ emissions to remain within 1.5°C of warming comes closer still, to around the mid-2030s. This is a strikingly different level of urgency to that evoked by the IPCC’s “early 2050s”. Similar smoke and mirrors lie behind the “early 2070s” timeline the IPCC conjures for limiting global heating to 2°C.

IPCC science embeds colonial attitudes

For over two decades, the IPCC’s work on cutting emissions (what experts call “mitigation”) has been dominated by a particular group of modellers who use huge computer models to simulate what may happen to emissions under different assumptions, primarily related to price and technology. I’ve raised concerns before about how this select cadre, almost entirely based in wealthy, high-emitting nations, has undermined the necessary scale of emission reductions.

In 2023, I can no longer tiptoe around the sensibilities of those overseeing this bias. In my view, they have been as damaging to the agenda of cutting emissions as Exxon was in misleading the public about climate science. The IPCC’s mitigation report in 2022 did include a chapter on “demand, services and social aspects” as a repository for alternative voices, but these were reduced to an inaudible whisper in the latest report’s influential summary for policymakers.

The specialist modelling groups (referred to as Integrated Assessment Modelling, or IAMs) have successfully crowded out competing voices, reducing the task of mitigation to price-induced shifts in technology – some of the most important of which, like so-called “negative emissions technologies”, are barely out of the laboratory.

The IPCC offers many “scenarios” of future low-carbon energy systems and how we might get there from here. But as the work of academic Tejal Kanitkar and others has made clear, not only do these scenarios prefer speculative technology tomorrow over deeply challenging policies today (effectively a greenwashed business-as-usual), they also systematically embed colonial attitudes towards “developing nations”.

With few if any exceptions, they maintain current levels of inequality between developed and developing nations, with several scenarios actually increasing the levels of inequality. Granted, many IAM modellers strive to work objectively, but they do so within deeply subjective boundaries established and preserved by those leading such groups.

What happened to equity?

If we step outside the rarefied realm of IAM scenarios that leading climate scientist Johan Rockström describes as “academic gymnastics that have nothing to do with reality”, it’s clear that not exceeding 1.5°C or 2°C will require fundamental changes to most facets of modern life.

Starting now, to not exceed 1.5°C of warming requires 11% year-on-year cuts in emissions, falling to nearer 5% for 2°C. However, these global average rates ignore the core concept of equity, central to all UN climate negotiations, which gives “developing country parties” a little longer to decarbonise.

Include equity and most “developed” nations need to reach zero CO₂ emissions between 2030 and 2035, with developing nations following suit up to a decade later. Any delay will shrink these timelines still further.

Most IAM models ignore and often even exacerbate the obscene inequality in energy use and emissions, both within nations and between individuals. As the International Energy Agency recently reported, the top 10% of emitters accounted for nearly half of global CO₂ emissions from energy use in 2021, compared with 0.2% for the bottom 10%. More disturbingly, the greenhouse gas emissions of the top 1% are 1.5 times those of the bottom half of the world’s population.

So where does this leave us? In wealthier nations, any hope of arresting global heating at 1.5 or 2°C demands a technical revolution on the scale of the post-war Marshall Plan. Rather than relying on technologies such as direct air capture of CO₂ to mature in the near future, countries like the UK must rapidly deploy tried-and-tested technologies.

Retrofit housing stock, shift from mass ownership of combustion-engine cars to expanded zero-carbon public transport, electrify industries, build new homes to Passivhaus standard, roll-out a zero-carbon energy supply and, crucially, phase out fossil fuel production.

Three decades of complacency has meant technology on its own cannot now cut emissions fast enough. A second, accompanying phase, must be the rapid reduction of energy and material consumption.

Given deep inequalities, this, and deploying zero-carbon infrastructure, is only possible by re-allocating society’s productive capacity away from enabling the private luxury of a few and austerity for everyone else, and towards wider public prosperity and private sufficiency.

For most people, tackling climate change will bring multiple benefits, from affordable housing to secure employment. But for those few of us who have disproportionately benefited from the status quo, it means a profound reduction in how much energy we use and stuff we accumulate.

The question now is, will we high-consuming few make (voluntarily or by force) the fundamental changes needed for decarbonisation in a timely and organised manner? Or will we fight to maintain our privileges and let the rapidly changing climate do it, chaotically and brutally, for us?

What he said…

“Our wise and noble leaders have just concluded the 27th annual global climate conference known as COP27. They all seem jolly pleased with what they’d all decided to achieve including really very sincere commitment to work super-duper hard to put in place policy that would definitely address the idea of thinking about doing things that might contribute towards the possibility of reducing greenhouse gas emissions with the aim of maybe limiting global temperatures to only 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. Then there were the 636 lobbyists—I mean delegates at COP27—representing the fossil fuel industry who reassured us all that increasing oil and gas exploration was actually an extremely important part of the transition toward achieving the 1.5 degrees Celsius target.”

The carbon budget: a moving target that politicians just moved beyond reach.

Bankrupting the Carbon Budget:

What tipping points mean for the carbon budget

In Bankrupting the Carbon Budget: Part I, tipping points were explained in Videos 1 and 2.

Others tipping points include wildfires in the Arctic and Australia. Together these released around 1Gt of CO2 in 2020. The devastation was so great in places that the conditions that led to the evolution of these ancient ecosystems no longer exist. ‘Zombie’ wildfires in boreal forests in Siberia and Canada and Alaska continue to burn peat underground over winter, re-igniting record-breaking forest fires in the summer of 2021.

These forests, which make up large parts of the biosphere that once absorbed carbon and locked it away, are now releasing carbon to the atmosphere together with human-caused emissions. They have passed a tipping point; a point of no return. The countdown clock in Fig. 1 doesn’t include these emissions because the compound effects are so complex, they have yet to be included in Earth systems models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

But the atmosphere doesn’t care where these emissions originate. Nor how much nations—most notably New Zealand—or businesses cheat on their carbon accounting. The reality is that the carbon budget is a globally shared account. Governments think they know how much we have left to ‘spend’, but the burning forests and melting permafrost and methane clathrates are making CO2 withdrawals over which we have no control. All we know is that somewhere between warming of 1-2°C, some tipping points will be irreversible and warming will accelerate, causing even more tipping points to fall like dominoes.

A race against time

The relationship between the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere and warming is well-understood physics and chemistry. But there is a delay—a lag time of 10-20 years—between adding CO2 to the atmosphere and warming. So even if we switch off all emissions today, things will get hotter over the next two decades. It takes even longer for melting icecaps to raise sea levels, unless there’s an abrupt Meltwater Event (historically, these have raised sea levels as much as 4m/century).

The IPCC is banking our future existence on the lag time to literally buy us time to drawdown enough CO2 from the atmosphere and permanently store it back where it came from, with fingers crossed that will return the planet to a safe operating space of 350ppm.

The Plan: built-in assumptions

The crucial thing about The Plan is that it depends entirely on assumptions. The most important assumption is that carbon capture technologies will draw down and safely store CO2 underground before warming triggers irreversible tipping points. This assumption (otherwise known as magical thinking) is because there isn’t enough land on Earth to plant enough trees to offset emissions while still being able to grow food to feed an exploding global population:

The Plan by the numbers: 2019 – 2050

- Atmospheric concentration at the start of 2019: 408ppm

- Emit: no more than 400Gt of CO2 over the next 21 years; this would add around 23ppm to the atmosphere.

- Offset emissions: as some emissions are unavoidable, they must be 100% offset by drawing down the same amount of CO2 as emitted and storing it permanently underground or in natural ecosystems. Plantation forestry is by definition not permanent, so it shouldn’t be regarded as a permanent offset because the carbon in it is recycled back into the atmosphere.

- Draw down: an average 3.9Gt of CO2 every year (total 81.9Gt between 2019-2050) and store it underground and in natural ecosystems. In total, this would remove around 10.5ppm. Again, plantation forestry shouldn’t be regarded as a permanent drawdown.

- Together, The Plan means that atmospheric concentration as of January 2050 will be: 408ppm + 23ppm – 10.5pm = 420.5ppm.

- Limitations to offsetting and drawdown:

- The world’s terrestrial ecosystems can only hold between 40 and 100Gt, so by 2050, CO2 will need to be permanently stored elsewhere.

- Burning forests and melting permafrost and methane clathrates are emitting CO2 and methane. We don’t know how much, we have no control over it, but we do know this is eating into the existing carbon budget.

The Plan by the numbers: 2050 – 2100

- The planned atmospheric concentration at the start of 2050: 420.5ppm

- Emit: zero CO2

- Offset: As some emissions are unavoidable, they must be 100% offset by drawing down the same amount of CO2 as emitted and storing it permanently underground. By now, terrestrial ecosystems will be unable to store any more carbon.

- Draw down average 24Gt/year until 2100 (24Gt x 50 years = 1,250Gt or 72ppm) and store it…somewhere.

- Planned atmospheric concentration at the start of 2100: 420.5ppm – 72ppm = 348.5ppm.

- Limitations to offsetting and draw down:

- Burning forests and melting permafrost and methane clathrates will be emitting far more CO2 and methane, so the budget will likely need further revision.

The Plan: how are we doing so far? 2019 – 2021

- Atmospheric concentration at the start of 2019: 408ppm

- Atmospheric concentration at start of 2022: 418ppm, ie, we’re going to hit 420.5pm before 2024, not 2050.

- Emitted: 107Gt of CO2 (26.7% of the 21-year budget ‘spent’ in 3 years)

- Offset: A handful of the world’s largest carbon polluters are buying up most of the land available for afforestation/reforestation to offset their emissions, leaving no available land for others to offset theirs. This includes land needed to feed people. Many are investing in low value or ‘ghost’ forests such as palm oil plantations, because plants that grow faster earn far more money from carbon credits. Many corporations have no plans to ever become carbon neutral because they will pass the cost of cheap and often useless offsets onto customers. The New Zealand Government, which is using taxpayer dollars to subside the eye-watering carbon cost of agriculture (giving them a 95% discount on emissions), and Fonterra, our largest carbon polluter, also plan to buy carbon credits offshore because they’re cheaper.

- Draw down: In spite of all the reforestation and rewilding projects around the globe, terrestrial ecosystem destruction (land use change) exceeded reforestation and offsetting by approximately 10Gt (Fig. 2). A large chunk of these losses are from the Amazon, parts of which have become so dry that they can no longer support re-forestation, so they’re turning in savannahs or being used to grow palm oil, soya, and methane-emitting cows.

- Limitations to offsetting and drawdown:

- Oddities with emissions trading schemes not accounting for the value of carbon locked in established forests and their soils, has created perverse incentives: old-growth and naturally regenerating forests are being cut down and/or burned so they can be replaced by fast growing monoculture crops like pine forests that earn more from carbon credits (if they survive wildfires and rapidly rising temperatures). And COP26 did nothing to prevent this from happening into the future (scroll down).

- The only company extracting CO2 and permanently storing it underground (versus selling it as fuel) is in Iceland. In September 2021, Climeworks’ operations scaled up. It now draws down and stores 4,000 tonnes CO2/year. To scale up to 3.9Gt/year (‘The Plan’) would require building and deploying 9.5 million additional fully operating plants of the same size. To scale up to 24Gt/year from 2050 onward would require 58.5 million additional fully operational plants of the same size. And then there’s this:

- Oddities with emissions trading schemes not accounting for the value of carbon locked in established forests and their soils, has created perverse incentives: old-growth and naturally regenerating forests are being cut down and/or burned so they can be replaced by fast growing monoculture crops like pine forests that earn more from carbon credits (if they survive wildfires and rapidly rising temperatures). And COP26 did nothing to prevent this from happening into the future (scroll down).

“No artificial machines that are even in the design stage will also clean our air, clean our water, provide habitat for wildlife and all the other useful features of trees.” – Sophie Bertazzo, Senior editor, Conservation International

COP26: bankrupting the carbon budget

COP26: The oceans

As Bonnie Waring said in the quote above:

“If we absolutely maximised the amount of vegetation all land on Earth could hold…”

The oddity in The Plan is that it largely ignores 70% of the surface of the planet that’s not land: the oceans, or more specifically the blue carbon in them. For the first time, the capability of the oceans to rapidly draw down and permanently store vast quantities of CO2 was finally addressed at COP26.

New Zealand has an exclusive oceanic economic zone 14 times larger than our land area. Why isn’t the government (and heavy carbon polluters) using that incredible capacity to invest far more in locally produced blue carbon? Fed by the sun, with no need for irrigation or agricultural chemicals, some species can grow up to 1m/day, drawing down as much as five times more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than rainforests, and permanently sequestering if not harvested and instead, cut and dropped into deep ocean.

Watch this (deep blue) space.

More information

- COP26: The final draft

- Glasgow’s 2030 credibility gap: net zero’s lip service to climate action: Climate Action Tracker

- Detailed analyses of each component of COP26: Carbon Brief (scroll down the page a bit to see the links to each section)

We need carbon. We need water, too. But like all good things, there can be too much. Too little water and we die of thirst. Too much, we drown. The same with carbon. Too little in the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide (CO2), we go into an Ice Age. Too much, the planet broils. We know this because of the geological evidence and from fundamental laws of physics and chemistry.

How much carbon is there?

There is about 1.85 billion, billion tonnes of carbon on Earth. More than 99% is beneath our feet in soil and rocks including fossil fuels and permafrost. Just 0.2% or 43,500Gt is above the surface. Through natural processes, carbon is constantly in flux. That is, it’s moving between the land, the oceans, and living things (see ‘carbon cycle’ this website). When it’s burned, melted, or respired, it becomes a gas, combining with oxygen to make CO2. Some ends up in the atmosphere*. The rest is absorbed by terrestrial and oceanic ecosystems: forests, grasslands, wetlands, and marine animals and plants that make more than half the oxygen we breathe, and also as carbonic acid (H2CO3) dissolved in ocean and lake waters.

*Calculations at the bottom of this page.

A shift in time

It doesn’t take much CO2 in the atmosphere to warm the planet. Some 18,000 years ago, the concentration of CO2 was 189 ppm (parts per million). Global temperatures were 7-9°C cooler than today, and ice sheets several kilometres thick covered most of Europe and North America.

Over the next 10,000 years, the concentration increased 72ppm, to reach 261ppm. That was enough to warm the planet 6-8°C (Fig 2.).

*The average for 2021 will be about 417ppm because atmospheric concentrations change between summer (lower) and winter (higher); see the graph below for an explanation.

The carbon budget

When governments signed the 2015 Paris Agreement they did so promising to keep global warming under 1.5°C by staying within a carbon budget. Each nation could choose how they would achieve this by reducing emissions—carbon ‘spending’—and increasing carbon ‘savings’ by planting carbon-absorbing trees. Obviously, to stay within the global budget, every nation had to play its part.

They didn’t. Emissions increased (Fig. 3)

And only if one-way climate tipping points, don’t tip.

Tipping points are tipping

“The drama here is that one characteristic of tipping points is that once you press the ‘on’ button you cannot stop it; it takes over. It’s too late. It’s not like you could say, ‘Oops, now I realize I didn’t want to melt the Greenland ice cap. Let’s back off.’ Then it’s too late.” – Johan Rockström, Breaking Boundaries: The Science of Our Planet (Video 1)