Causes: Methane CH4 – biogenic & ‘natural’ gas

Dairy cows are our single largest source – image Monika Kubala | Drilliing for gas – image J. Penrose

Causes

- A brief history of climate change: who knew what, when

- What causes climate change?

- Would the climate be warming without humans?

- Is it just a cycle? (Earth’s wobbly orbit)

- Sunspots & solar activity

- Land use: agriculture & cities

- Volcanoes

- Ocean currents

- Black carbon & ash

- Hydrogen

- Greenhouse gases & how they work

- – Carbon dioxide & the carbon cycle

- – Methane: biogenic (mostly cows) & ‘natural’ gas

- – Nitrous oxide

- – Clouds & water vapour

- – Ozone

- – Man-made industrial chemicals

- – Aerosol pollution

- How to start an Ice Age!

- What’s in a name?

Other sections

Home > Climate wiki > What causes climate change? > Greenhouse gases > Methane

Methane (CH4): biogenic & ‘natural’ gas

Summary

- Methane is created though biological process.

- Natural gas is methane; it is not a climate-friendly alternative or low-emissions transition energy!

- During the first 20 years after methane is emitted into the atmosphere, it has 84 x the global warming potential of CO2; ~50% of warming happens within 12.4 years, after which some breaks down into CO2, adding to existing warming potential.

- The amount of methane in the atmosphere is 2.5 times above pre-industrial levels and increasing (Fig. 1) mostly due to agriculture and the natural-gas industry.

- Methane is entering the atmosphere far faster than models anticipated. This is in part due to the feedback effect of warming which is melting vast areas of permafrost and some wetlands, and in part due to the reduction of pollution in emissions that helped methane breakdown.

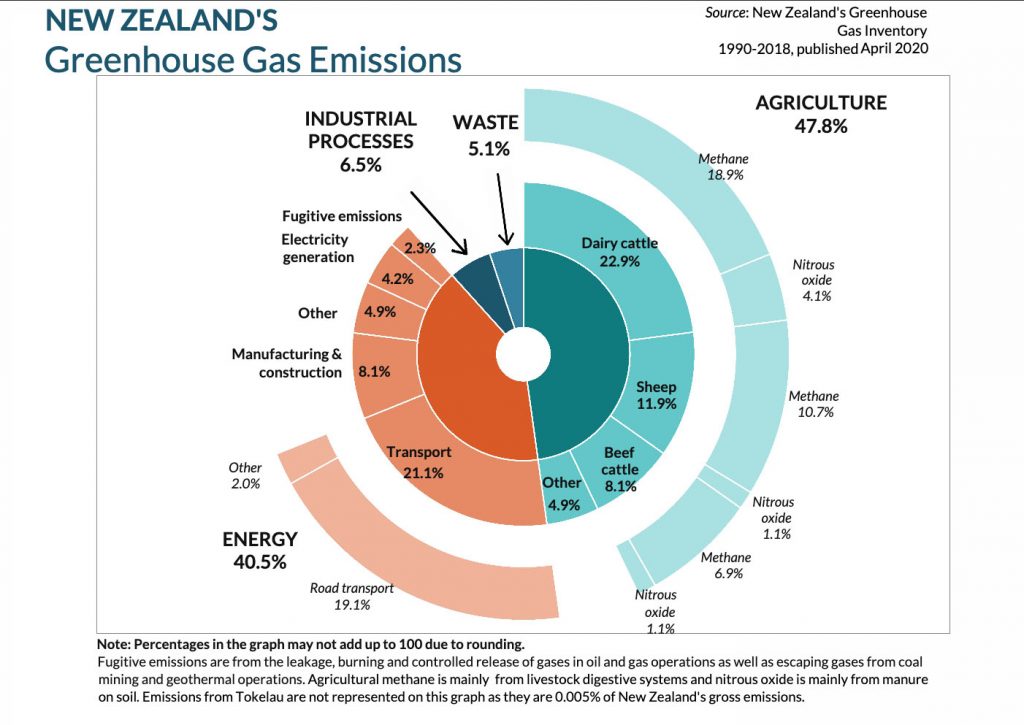

- Methane from agriculture accounts for 36.5% of NZ’s greenhouse gases—our largest single contribution by sector. As a result, NZ has the largest methane emission rate per person/year (0.6t) in the world—six times the global average.

- Under the NZ Emissions Trading Scheme and Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Act, agriculture has been given a free pass, ignoring the economic benefits of reduction and the catastrophic implications for a livable climate:

“The global monetized benefits for all market and non-market impacts are approximately US$4,300 per tonne of methane reduced. When accounting for these benefits nearly 85% of the targeted measures have benefits that outweigh the net costs. The benefits of the annually avoided premature deaths alone from a 1.5°C-consistent-methane mitigation strategy is approximately US$450 billion per year.” – UN Global Methane Assessment 2021

“Without strengthening mitigation efforts, greenhouse gas emissions are projected to lead to warming of 3.2C degrees. To limit warming to 1.5 degrees requires global greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest and be reduced by 43% by 2030. Emissions from methane…need to be reduced by about a third by 2030. Even if we do this it is almost inevitable that we will at least temporarily exceed 1.5C.” – Jim Shea, IPCC 2022: Mitigation (Video 2)

- Growing grass does not offset agricultural emissions:

“Grassland carbon stocks would need to increase by approximately 25% − 2,000%, indicating that solely relying on carbon sequestration in grasslands to offset warming effect of emissions from current ruminant systems is not feasible.” – Wang et al, 22 November, 2023

- MethaneSat to monitor methane emissions including those across Aotearoa is now in orbit.

Causes

- A brief history of climate change: who knew what, when

- What causes climate change?

- Would the climate be warming without humans?

- Is it just a cycle? (Earth’s wobbly orbit)

- Sunspots & solar activity

- Land use: agriculture & cities

- Volcanoes

- Ocean currents

- Black carbon & ash

- Hydrogen

- Greenhouse gases & how they work

- – Carbon dioxide & the carbon cycle

- – Methane: biogenic (mostly cows) & ‘natural’ gas

- – Nitrous oxide

- – Clouds & water vapour

- – Ozone

- – Man-made industrial chemicals

- – Aerosol pollution

- How to start an Ice Age!

- What’s in a name?

Other sections

Home > Climate wiki > What causes climate change? > Greenhouse gases > Methane

Summary

- Methane is created though biological process.

- Natural gas is methane; it is not a climate-friendly alternative or low-emissions transition energy!

- During the first 20 years after methane is emitted into the atmosphere, it has 84 x the global warming potential of CO2. ~50% of warming happens within 12.4 years, after which some breaks down into CO2, adding to existing warming potential.

- The amount of methane in the atmosphere is 2.5 times above pre-industrial levels and increasing (Fig. 1) mostly due to agriculture and the natural-gas industry.

- Methane is entering the atmosphere far faster than models anticipated. This is in part due to the feedback effect of warming which is melting vast areas of permafrost and some wetlands, and in part due to the reduction of pollution in emissions that helped methane breakdown.

- Methane from agriculture accounts for 36.5% of NZ’s greenhouse gases—our largest single contribution by sector. As a result, NZ has the largest methane emission rate per person/year (0.6t) in the world—six times the global average.

- Under the NZ Emissions Trading Scheme and Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Act, agriculture has been given a free pass, ignoring the economic benefits of reduction and the catastrophic implications for a livable climate:

“The global monetized benefits for all market and non-market impacts are approximately US$4,300 per tonne of methane reduced. When accounting for these benefits nearly 85% of the targeted measures have benefits that outweigh the net costs. The benefits of the annually avoided premature deaths alone from a 1.5°C-consistent-methane mitigation strategy is approximately US$450 billion per year.” – UN Global Methane Assessment 2021

“Without strengthening mitigation efforts, greenhouse gas emissions are projected to lead to warming of 3.2C degrees. To limit warming to 1.5 degrees requires global greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest and be reduced by 43% by 2030. Emissions from methane…need to be reduced by about a third by 2030. Even if we do this it is almost inevitable that we will at least temporarily exceed 1.5C.” – Jim Shea, IPCC 2022: Mitigation (Video 2)

- Growing grass does not offset agricultural emissions:

“Grassland carbon stocks would need to increase by approximately 25% − 2,000%, indicating that solely relying on carbon sequestration in grasslands to offset warming effect of emissions from current ruminant systems is not feasible.” – Wang et al, 22 November, 2023

- MethaneSat to monitor methane emissions including those across Aotearoa is now in orbit.

Instructions for interactive graphs (Credit: The 2°Institute.)

- Mouse over anywhere on the graphs to see the changes over the last thousand years.

- To see time periods of your choice, hold your mouse button down on one section then drag the mouse across a few years, then release it.

- To see how this compares to the past 800,000 years, click on the ‘time’ icon on the top left.

- To return the graphs to their original position, double-click the time icon.

Instructions for interactive graphs (Credit: The 2°Institute.)

- Mouse over anywhere on the graphs to see the changes over the last thousand years.

- To see time periods of your choice, hold your mouse button down on one section then drag the mouse across a few years, then release it.

- To see how this compares to the past 800,000 years, click on the ‘time’ icon on the top left.

- To return the graphs to their original position, double-click the time icon.

-

Methane is produced by single-celled ‘methanogenic’ microorganisms that feed on plants in anaerobic (oxygen-free) conditions. They are vital microorganisms because the help decay dead plants and animals. This helps to recycle the nutrients back into the food chain. In the same way that we and other animals breath out carbon dioxide as a waste product, these organisms release methane is a waste product. Methanogenic microorganisms are some of the oldest forms of life on Earth (Archaea) and they’re found everywhere, including in some trees.

Most of the methane they produce is absorbed back into the ground. Much was locked away for many millions of years along with coal (which is why it’s so often found in coal mines) and during the most recent Glacial epoch as frozen clathrates. However, clathrates are now defrosting (see the tab below) the microbes have sprung back into life, and methane is escaping into the atmosphere at a rapidly accelerating rate.

Methane that escapes into the atmosphere takes about 12 years to break down into carbon dioxide (CO2) and enters the carbon cycle.

The New Zealand Greenhouse Gas Inventory report summarised in the graph below uses a range of parameters to assess how much methane is produced by different activities. Some of this is based on estimates, others on actual measurements. Agriculture produces 36.5%. (Image credit: New Zealand Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990-2018 [April 2020]).

Research published February 2020 revealed a way to distinguish emission from biogenic sources—agriculture, livestock etc—and fossil fuel sources.

Click on the following tabs to find out more about the sources of methane.

-

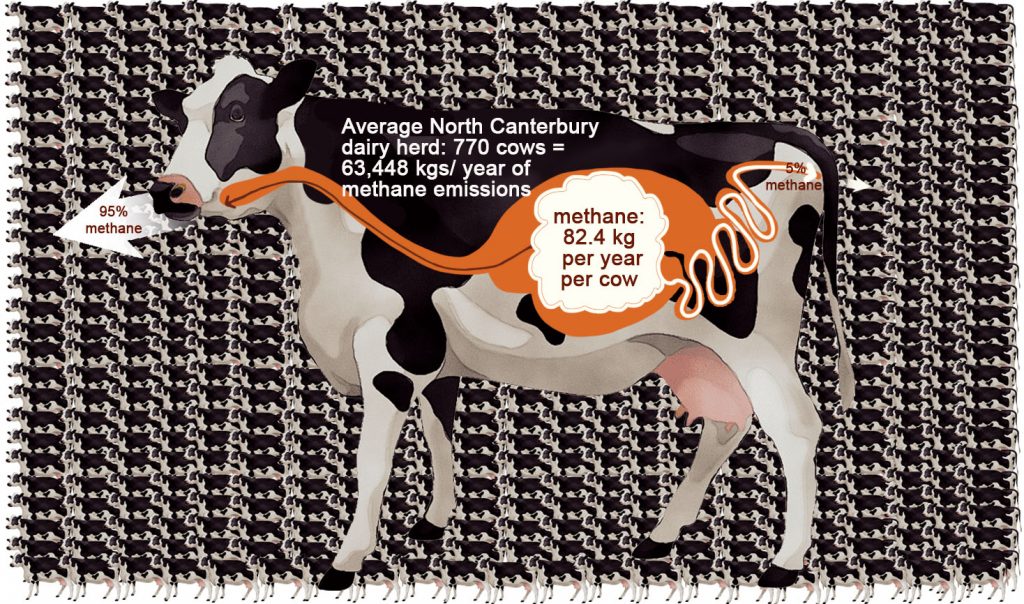

Ruminant animals, primarily sheep and cows, are the largest producer of anthropogenic methane gas in Aotearoa (see the round graph in the tab above).

Methanogenic microorganisms live in the gut of these animals to breakdown the food using a process called enteric fermentation (Fig. 3).

- A sheep can produce ~30 litres of methane/day

- A dairy cow can produce up to ~200 litres/day.

Here in New Zealand, the number of dairy cows in Canterbury increased from 490 in 1994 to 1,253,993 in 2015.

This has and continues to result in huge quantities of methane escaping into the atmosphere directly from the animals, through effluent ponds, and also by adding fertiliser to land.

While enteric fermentation is natural in grazing animals, around the world, particularly in places like Brazil, humans have burned down millions of hectares of forest and wetlands that once recycled methane efficiently, with millions of domesticated ruminants that graze on grass or are fed grains from grasses.

-

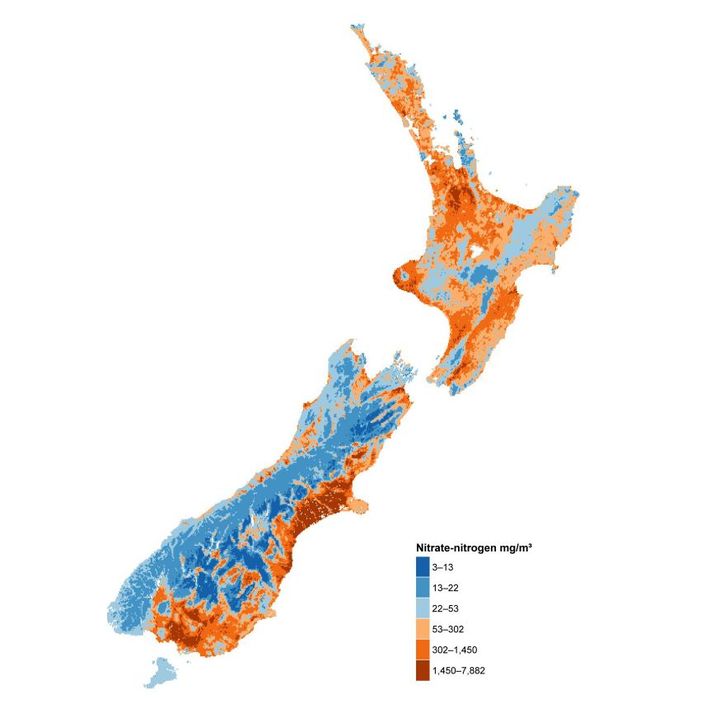

Effluent pondsCow dung and urine from milking sheds, concrete ‘stand-off’ pads, and permanent indoor housing is washed into these ponds. Here, bacteria and methanogenic microbes break down the effluent, producing methane and nitrous oxide (a greenhouse gas 298 times more warming potential than carbon dioxide). As dairy farming is intensified to industrial scales, more effluent will be collected this way.“Results from our investigation indicate that the national GHG Inventory is currently underestimating dairy effluent pond CH4 emissions by a factor of 1.7 to 4. Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) noted that: ‘Currently there is widespread interest in removing animals from pastures and placing them on stand-off pads or more permanent housing.’ If this shift in animal management occurs, it would have an enormous impact on the way that dairy effluent is managed. The time that cows spend on sealed surfaces would increase, so that more manure would need to be treated by effluent ponds, resulting in higher CH4 emissions. If a much higher proportion of the total daily dairy cow waste production is collected, and manure management practices are not changed, manure CH4 emissions have the potential to equal the current main agricultural GHG sources of enteric methane and pasture nitrous oxide emissions.” – MPI reportCoes Ford, Selwyn River – photo: Fish and Game)FertilisersAbove is a photo is of an algae bloom at Coes Ford in mid-Canterbury. To fertilise the grass to feed dairy cows, nitrogen and phosphorus are added in huge quantities to the soil of dairy farms in Canterbury. Some of this fertilizer runs off into streams and rivers. These nutrients fertilise algae just as they fertilise grass, so algae flourishes. Especially in summer when river levels are often lower and temperatures are higher (and increasing with climate change), the algae blooms overwhelm the water’s oxygen resources, killing other aquatic plants and animals. When the algae dies, it’s decomposed by bacteria and methanogens, which release both CO2 and methane into the atmosphere. This is major issue for waterways, particularly Canterbury’s braided rivers.

Nitrate-nitrogen content in New Zealand waterways. Note the extremely high rates in Canterbury rivers (dark red) vs natural and largely uncultivated landscapes in alpine areas and Fjordland (blue). (Image: Ministry for the Environment).

-

While very little rice is grown in New Zealand, globally ~3.5 billion people depend on rice for more than 20% of their daily calories and ~1 billion depend on it for their income. The conditions in which rice is grown are ideal for bacteria and methanogens to produce methane and nitrous oxide (a greenhouse gas 298 times more potent than CO2). Perversely, techniques intended to reduce emissions while also cutting water use, may be increasing emissions, meaning methane from rice cultivation may be up to twice as bad as previously estimated.

Agriculture, particularly vast areas being converted to rice growing, is one of the reasons cited for why greenhouse gasses gradually began increasing in the atmosphere thousands of years ago, long before fossil fuels started to be burned to produce energy.

Rice is is such demand globally that in many Asian and South East Asian countries like the Philippines where this photo was taken, entire hills and mountains have been re-sculptured over centuries, possibly millennia in some places, to grow rice on terraces. (Image: Wikipedia CC license.)

-

For many decades, dams built to produce hydro-electricity we seen as a clean alternative to burning fossil fuels. However, when a river is dammed, the blocked water that builds up behind it creates an unnatural, stagnant lake that eventually kills most of the original ecosystem that once existed there. Everything—plants, forests, the insects, microorganisms and fungi in the soils crucial for sequestering carbon—are all drowned. Bacteria and methanogens in the lake decompose the dead, emitting CO2 and methane. This bubbles to the surface adding more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

While this may not apply to New Zealand, research is yet to be done:

“The wider research could have implications for the idea, currently being investigated by the government, to build a pumped hydro dam at Lake Onslow. It’s likely any additional methane will be small compared to the emissions saved from keeping fossil fuels in the ground.” – Stuff article, 2021.

When you flush the toilet or wash water down the drain, the wastewater goes to where its treated. In rural areas that’s a septic tank in your backyard. In urban areas and cities, it goes to giant Council- run treatment plants. Different industries – mining, dairy, wine, wool, leather, meat, each have their own wastewater treatment plants as well. In all cases, at some stage in the treatment process, bacteria and methanogens decompose the organic waste. This produces carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide (a greenhouse gas 298 times with more warming potential than CO2), and methane in a similar way that happens in effluent ponds. Depending on how efficient the treatment is and how the gasses are dealt with, some of these gasses escape into the atmosphere.

-

Burning coal and oil releases methane. Recently, New Zealand scientists, amongst others, have determined that burning fossil fuels is adding 35-40% more methane into the atmosphere than previously thought (ie, it is is not yet included in current inventory calculations). In addition to this, burning methane releases CO2 in the atmosphere.

Industry: A small amount of methane is produced during these processes, including cement and methanex manuafacturing, both of which take place in New Zealand. These are accounted for in different ways in the New Zealand Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990-2017.

Fugitive emissions happen because methane is less dense than air, so its lighter, which means it can easily escape into the atmosphere during mining, transport, manufacturing, and storage—including escaping from the gas bottles used for BBQs. As it’s highly flammable, any gas that builds up too much pressure must be vented, ie leaked into the atmosphere. Some but not all mines burn some of this excess gas in a process called ‘flaring’.

“In 2017, fugitive emissions from the Oil and natural gas category contributed 1,808.2 kt CO2-e (93.2 per cent) to emissions from the Fugitive emissions category. This is an increase of 799.3 kt CO2-e (79.2 per cent) from 1,008.9 kt CO2-e in 1990.” – New Zealand Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990-2017 p107

-

Globally, millions of hectare of forest is burned every year. Sometimes this is a result of climate-related rising temperatures and drought, such as in the Australian 2019-2020 bushfires, where 18.6 million hectares (46 million acres) was burned. Some Boreal forest fires exhibit ‘overwintering’ behaviour, in which they smoulder through the non-fire season and flare up in the subsequent spring.

In the Brazilian Amazon (image below), in August 2019 alone, close to 2.5 million hectares of land was burned by farmers to produce soya and beef specifically to sell to overseas buyers including McDonald’s, Burger King, and Kentucky Fried Chicken.

While forest fires are not yet a huge concern for New Zealand in terms of methane emissions, the increasing risks need to be considered in light of the impetus to plant millions of pine trees instead of native forests. Pine plantations extend lifetime of methane in the North Island atmosphere.

-

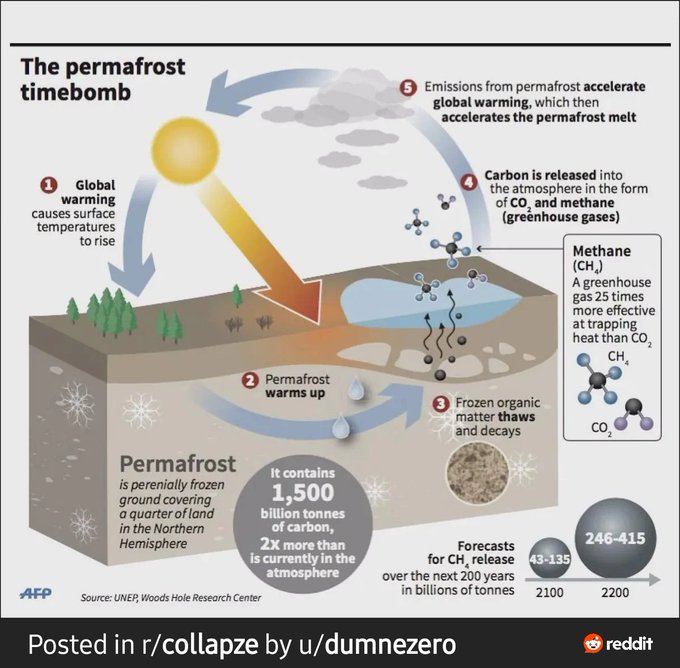

Permafrost is a combination of soil, sediment, and the remains of dead plants and animals that stay at or below 0°C for at least two years. Unlike ice, it doesn’t ‘melt’ once temperatures rise above 0°C. Permafrost falls apart, and the organic material decomposes, just as frozen meat or vegetables left outside a freezer will decompose if not eaten. When this decomposition happens an environment where there’s oxygen, such as outside your fridge on the sink, carbon dioxide is released. If the environment is anaerobic (lacks oxygen), such as underwater in lakes, wetlands, and the ocean, methane is released (Video).

Permafrost can be as thin as <1m and as thick as >1,000m. It covers approximately 22.79 million km² (about 24% of the exposed land surface) of the Northern Hemisphere.

Melting permafrost is the result of a feedback effect of climate change, that is anthropogenic forcing is a triggering natural forcing.

In 2019, NOAA estimated that melting permafrost was contributing 600 million metric tonnes of net carbon (methane and carbon dioxide) per year into Earth’s atmosphere.

“By 2100, near-surface permafrost area will decrease by 2-66% for RCP2.6 and 30–99% for RCP8.5. This could release 10s to 100s of gigatonnes of carbon as CO2 and methane to the atmosphere.” – IPCC, 2019

The first few minutes of the following video shows what happens when this escaping methane is ignited.

Permafrost time bomb

-

Permafrost is a combination of soil, sediment, and the remains of dead plants and animals that stay at or below 0°C for at least two years. Unlike ice, it doesn’t ‘melt’ once temperatures rise above 0°C. Permafrost falls apart, and the organic material decomposes, just as frozen meat or vegetables left outside a freezer will decompose if not eaten. When this decomposition happens an environment where there’soxygen, such as outside your fridge on the sink, carbon dioxide is released. If the environment is anaerobic (lacks oxygen), such as underwater in lakes, wetlands, and the ocean, methane is released (Video).

Permafrost can be as thin as <1m and as thick as >1,000m. It covers approximately 22.79 million km² (about 24% of the exposed land surface) of the Northern Hemisphere.

Melting permafrost is the result of a feedback effect of climate change, that is anthropogenic forcing is a triggering natural forcing.

In 2019, NOAA estimated that melting permafrost was contributing 600 million metric tonnes of net carbon (methane and carbon dioxide) per year into Earth’s atmosphere.

“By 2100, near-surface permafrost area will decrease by 2-66% for RCP2.6 and 30–99% for RCP8.5. This could release 10s to 100s of gigatonnes of carbon as CO2 and methane to the atmosphere.” – IPCC, 2019

The first few minutes of the following video shows what happens when this escaping methane is ignited.

Permafrost time bomb

-

Methane clathrate (also called methane hydrate, fire ice, hydromethane, methane ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate), is methane frozen in a crystal structure of water, forming a solid that looks like ice. Once thought to exist only in the frozen outer parts of the Solar System, it turns out to abundant in permafrost and beneath the ocean floor.

The United States Geological Service (USGS) estimates the amount of carbon in methane clathrates is twice the amount of carbon that exists in all the fossil fuels on Earth.While the USGS regard it as potential source of fuel, the sheer volume of what’s being released naturally, has alarming consequences. As one cubic metre of methane hydrate produces between 163-180 metres of gas, the explosive potential is also high.Video 1 explores, amongst other impacts, how methane ‘burps’ from melting permafrost and methane clathrates are forming large craters in Siberia. The peer-reviewed open access research paper by Shakova et al is here.Video 2 below explains that large scale melting of clathrates in 2020 after Siberia experienced temperatures up to 45C.

-

Methane clathrate (also called methane hydrate, fire ice, hydromethane, methane ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate), is methane frozen in a crystal structure of water, forming a solid that looks like ice. Once thought to exist only in the frozen outer parts of the Solar System, it turns out to abundant in permafrost and beneath the ocean floor.

The United States Geological Service (USGS) estimates the amount of carbon in methane clathrates is twice the amount of carbon that exists in all the fossil fuels on Earth.

While the USGS regard it as potential source of fuel, the sheer volume of what’s being released naturally, has alarming consequences. As one cubic metre of methane hydrate produces between 163-180 metres of gas, the explosive potential is also high.Video 1 explores, amongst other impacts, how methane ‘burps’ from melting permafrost and methane clathrates are forming large craters in Siberia. The peer-reviewed open access research paper by Shakova et al is here.Video 2 below explains that large scale melting of clathrates in 2020 after Siberia experienced temperatures up to 45C.

-

Video1 was recorded at COP26 in 2021. The presentations may appear somewhat dry at the outset, but the current science indicates that this tipping point is extremely close. In December 2022, with methane levels accelerating, there is growing concern than permafrost and clathrate melting has now passed a tipping point: Video 2.

-

Gas used in BBQs can include higher alkanes (gasses with more carbon in their molecular structure than methane), and sometimes small amounts of other gasses: carbon dioxide, nitrogen, hydrogen sulfide, and/or helium.

Methane has no colour or smell, but it’s highly flammable, which is why it’s used for cooking. In many countries including New Zealand an ‘odourant’ or ‘stenching’ (i.e. a distinctive bad smell) is added so that it can easily be detected in case it leaks.

The bad smell coming from rotting vegetation or effluent ponds is NOT methane; it’s other gasses including hydrogen sulfide and ammonia.

-

The term ‘climate forcing’ comes from ‘radiative forcing’ or RF, which is the difference between the amount of solar energy reaching Earth’s atmosphere and the amount that escapes. If more solar energy escapes than arrives, the planet cools. Conversely, if less energy escapes than gets in, the planet warms.

Click here to learn about the main forcings and how they work (links to a page on this site).

-

The transition of many human cultures from hunting and gathering to agriculture began ~12,000 to 15,000 years ago, around the time the last Glacial Maximum ended.

From ~11,500 years ago the global climate began stabilising enough for agriculture to spread. By 9,000 years ago agriculture was common in many places and by ~6,000 years ago, rice growing was a common practice in many areas.

At the same time, the Earth’s climate was slowly moving into a natural cooling phase.

Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture have been credited with offsetting this very slight, very gradual cooling, thereby maintaining a relatively stable temperature until the Industrial Revolution, which was was powered by burning huge quantities of fossil fuels that releasing unprecedented quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

-

The global warming potential or radiative forcing (RF) of methane is calculated as ’25’ under the NZ Emissions Trading Scheme. This measurement is based on the average effect is has in the atmosphere over 100 years.

- Total methane emissions from a single dairy cow/year: enteric fermentation + manure management + soil = 2060kg CO2-e

- The average North Canterbury dairy herd is 770 cows

These emissions are currently EXEMPT from the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme.

-

- 2024: MethaneSAT now in orbit

- 2024: Davies et al; Long-distance migration and venting of methane from the base of the hydrate stability zone, Nature Geoscience 17

- 2024; Hu et al; Relative increases in CH4 and CO2 emissions from wetlands under global warming dependent on soil carbon substrates, Nature Geoscience 17

- 2023: Wang et al; Risk to rely on soil carbon sequestration to offset global ruminant emissions, Nature Communications 14 | 7625 (Open access)

- 2023: Nisbet et al; Atmospheric Methane: Comparison Between Methane’s Record in 2006–2022 and During Glacial Terminations (tipping point) Global Biogeochemical Cycles AGU (Open access)

- 2023: Loomis; Why Natural Gas isn’t a Bridge Fuel to a Low Emissions Economy, Fossil Fuels Aotearoa Research Network

- 2023: Rocher-Ross et al; Global methane emissions from rivers and streams, Nature article August 2023 (open access)

- 2023: Kleber et al; Groundwater springs formed during glacial retreat are a large source of methane in the high Arctic, Nature Geoscience 16 pp597-604

- 2022: Peng et al; Wetland emission and atmospheric sink changes explain methane growth in 2020, Nature 612, pp477–482 (2022)

- 2022: Macnamara, Study explains surprise surge in methane during pandemic lockdown, Physics.org article explaining the above research in plain English

- 2022: NASA; Alaska’s Newest Lakes Are Belching Methane

- 2021: World Meterological Organisation/United Nations: United in Science 2021

- 2021: UN Report Global Methane Assessment: Benefits and Costs of Mitigating Methane Emissions

- 2021: Harrison et al; Year-2020 Global Distribution and Pathways of Reservoir Methane and Carbon Dioxide Emissions According to the Greenhouse Gas from Reservoirs (G-res) Model, AGU:Global Biogeochemical cycles (in print)

- European Space Agency (ESA) : Mapping methane emissions on a global scale

- Ministry for the Environment: New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme

- Ministry for the Environment: Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act

- Ministry for the Environment: New Zealand’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2017 Vol 1; Chapters 1-15

- Ministry for the Environment: New Zealand’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2017: graphic

- Ministry for the Environment: 2019 Measuring Emissions: A Guide for Organisations

- Ministry for the Environment: 2019 Measuring Emissions: A Guide for Organisations. 2019 Summary of Emission Factors

- Ministry for the Environment: Our Fresh Water 2017

- Ministry for the Environment: (rivers) Nitrate–nitrogen, 2009–2013

- Ministry for the Environment: Proposed National Environmental Standard to Control Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Landfills

- Ministry for Primary Industries: Agricultural Inventory Advisory Panel

- Atmospheric methane measurements (interactive)

- The New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC)

- Maanaki Whenua Landcare Research: Agricultural greenhouse gasses

- Maanaki Whenua Landcare Research: Methane emissions

- Bioninja Australia: Methane

- Terra Brasilis: online mapping data Brasil

- Wikipedia: Summary of 2019-2020 Australian bushfires

- NSIDC: State of the Cryosphere: Permafrost and Frozen Land

- 2021: Scholten et al; Overwintering fires in boreal forests, Nature 593, pp399–404

- 2020: McCalley; Methane Eating Microbes, Nature Climate Change 10, pp275–276

- 2020: Schiermeier; Global methane levels soar to record high Nature news article 14 July

- 2020: Saunos et al; The Global Methane Budget 2000–2017 Earth Systems Data Science 12 pp1561-1623

- 2020: Jackson; Increasing anthropogenic methane emissions arise equally from agricultural and fossil fuel sources Environmental Research Letters 15/7

- 2020: Thurber et al; Riddles in the cold: Antarctic endemism and microbial succession impact methane cycling in the Southern Ocean Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 22 July 2020

- 2020: Hmiel et al; Preindustrial 14CH4 indicates greater anthropogenic fossil CH4 emissions Nature 578, 409–412

- Good article in NZ Herald explaining this research, 20 February, 2020

- 2020: Kholod et al; Global methane emissions from coal mining to continue growing even with declining coal production Journal of Cleaner Production 256, 20 May 2020, 120489

- 2020: Zhang et al; Fingerprint of rice paddies in spatial–temporal dynamics of atmospheric methane concentration in monsoon Asia Nature Communications 11, 1–11

- 2020: McCalley; Methane-eating microbes Nature Climate Change 10, 275–276

- 2020: Scientific American news article: Methane Levels Reach an All-Time High

- 2019: Shakova et al; Understanding the Permafrost–Hydrate System and Associated Methane Releases in the East Siberian Arctic Shelf; Geosciences 9(6), 251

- 2019: Chuvilin (ed.) Special Issue “Gas and Gas Hydrate in Permafrost” A special issue of Geosciences (ISSN 2076-3263)

- 2019: NOAA Richter-Menge et al; Arctic Report Card 2019

- 2019: National Geographic: The Arctic Is Heating Up September 2019 special issue

- 2019: Nisbet et al; Very Strong Atmospheric Methane Growth in the 4 Years 2014–2017: Implications for the Paris Agreement, Global Biogeochemical Cycles 33/3 pp318-342

- 2019: Burunda; See how much of the Amazon is burning, how it compares to other years National Geographic magazine

- 2019: IPCC; Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories

- 2019: IPCC: Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Chapter 3: Polar Regions (Section 3.4: Arctic Snow, Freshwater Ice and Permafrost: Changes, Consequences and Impacts)

- 2018: Kritee et al; High nitrous oxide fluxes from rice indicate the need to manage water for both long- and short-term climate impacts PNAS 115 (39) 9720-9725

- 2018: Alvarez et al; Assessment of methane emissions from the U.S. oil and gas supply chain Science 361, 6398 pp186-188

- 2016: Schwietzke et al; Upward revision of global fossil fuel methane emissions based on isotope database Nature 538, 88–91

- 2016: Deemer et al; Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Reservoir Water Surfaces: A New Global Synthesis BioScience 66(11) 949–964

- 2012: Revised methane emission factors and parameters for dairy effluent ponds Ministry for Primary Industries report

- 2001 USGS: Gas Hydrates vast resource (fact sheet)

- 2000: St. Louis et al; Reservoir Surfaces as Sources of Greenhouse Gases to the Atmosphere: A Global Estimate: Reservoirs are sources of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, and their surface areas have increased to the point where they should be included in global inventories of anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases BioScience 50 (9) 766–775

- 2024: MethaneSAT now in orbit

Methane clathrate (also called methane hydrate, fire ice, hydromethane, methane ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate), is methane frozen in a crystal structure of water, forming a solid that looks like ice. Once thought to exist only in the frozen outer parts of the Solar System, it turns out to abundant in permafrost and beneath the ocean floor.

Methane clathrate (also called methane hydrate, fire ice, hydromethane, methane ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate), is methane frozen in a crystal structure of water, forming a solid that looks like ice. Once thought to exist only in the frozen outer parts of the Solar System, it turns out to abundant in permafrost and beneath the ocean floor.