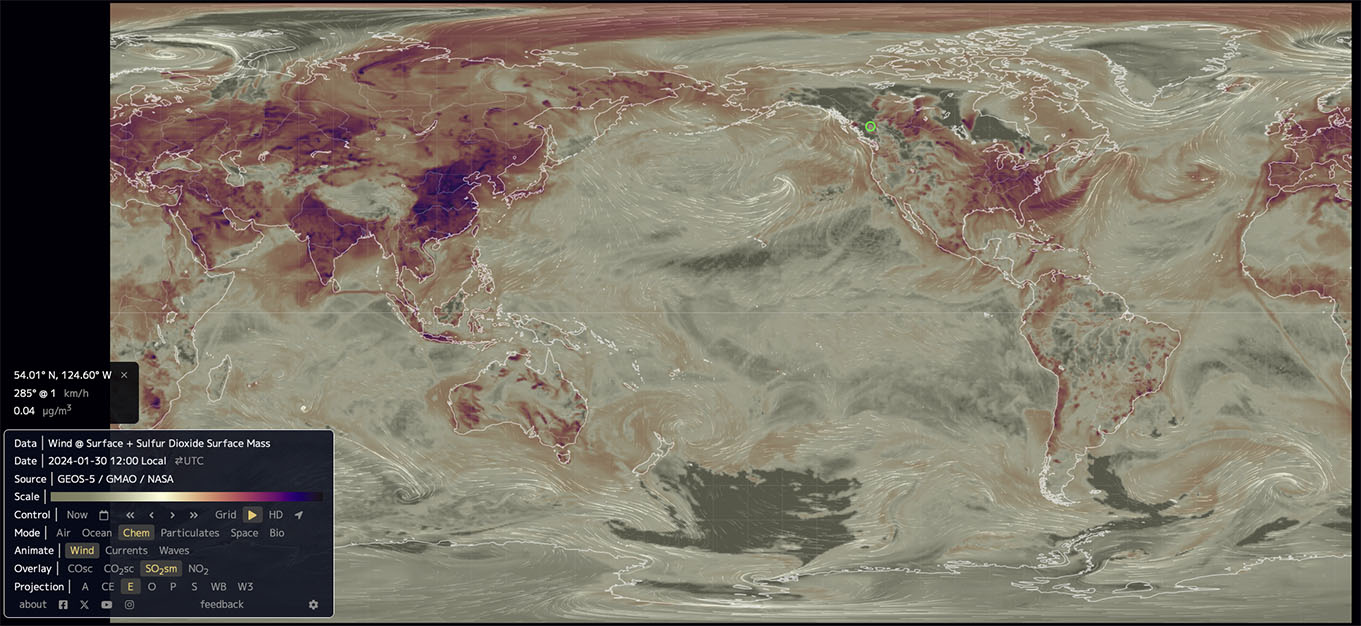

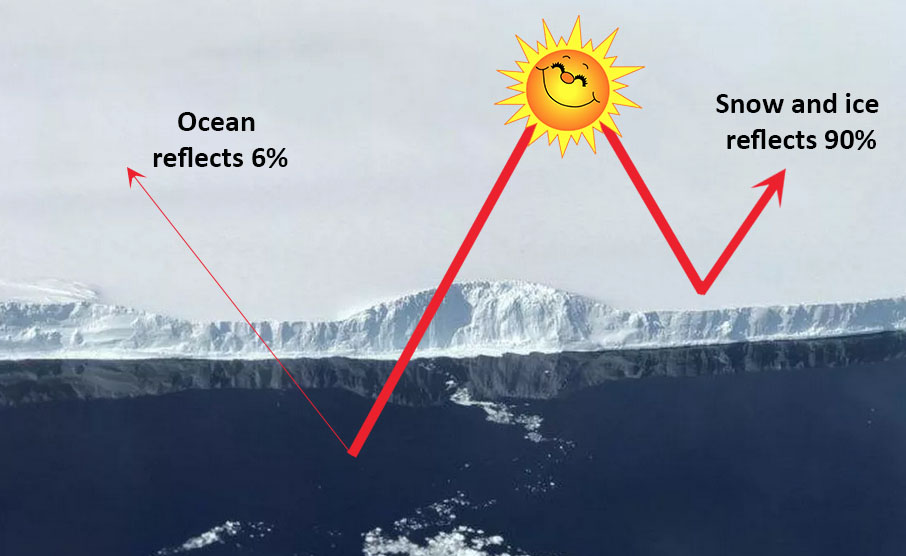

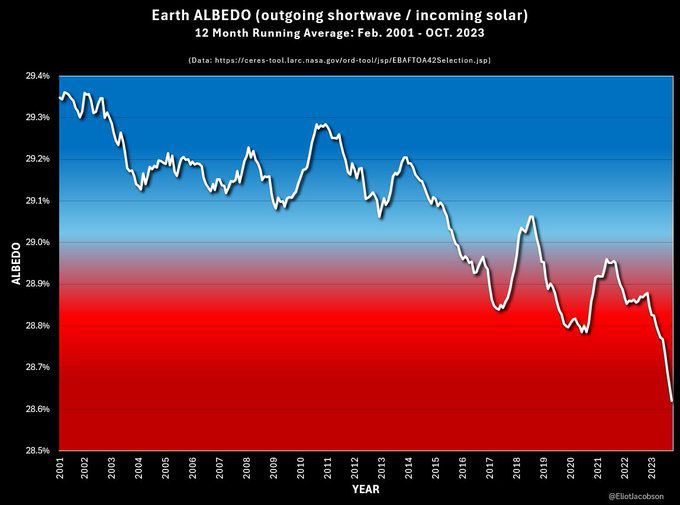

Causes: Cooling effect of emissions

Image: Peggy Anke

Video 1: November 2022 Dr. Ye Tao explains research that critiques the IPCC 6th Assessment Report (2021) use of the lowest estimate of 0.7C, when the range is much higher. As the IPCC has consistently underestimated the speed and impacts of climate change, Tao argues that it would be prudent to prepare for a higher figure.

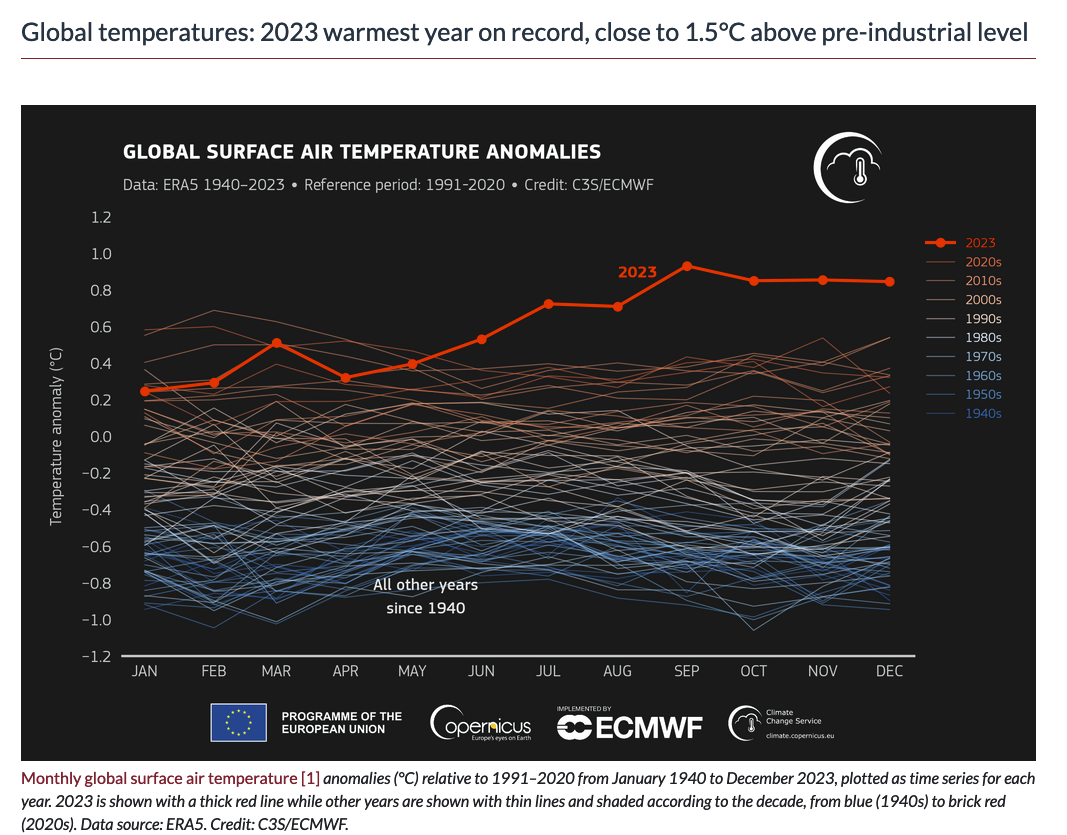

Video 2: January 2024, Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson & Dr. Gavin Schmidt, climate modeler and Director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, discuss why the record breaking temperatures in 2023 was due primarily to the decline in aerosols, as predicted by Tao and Hansen (Video 1).

Video 3: Methane comes from production and transport of fossil fuels, but instead of tumbling during the global COVID lockdowns, they spiked upwards.