Nature-based solutions: Oceans

Plankton bloom image: NASA Earth Observatory

“Marine sediments are the largest pool of organic carbon on the planet and a crucial reservoir for long-term storage. If left undisturbed, organic carbon stored in marine sediments can remain there for millennia. However, disturbance of these carbon stores can re-mineralize sedimentary carbon to CO2, which is likely to increase ocean acidification, reduce the buffering capacity of the ocean and potentially add to the build-up of atmospheric CO2. Thus, protecting the carbon-rich seabed is a potentially important nature-based solution to climate change... Eliminating 90% of the present risk of carbon disturbance due to bottom trawling would require protecting 3.6% of the ocean.” – Sala et al, 2021

“By drastically reducing fish biomass over the past century, industrial fishing may be affecting ocean chemistry, nutrient fluxes,and carbon cycling as much as climate change.” – Zimmer, 2021.

The problems

The ocean is a world where gravity poses no limits. Billions of creatures great and small live all the way up through the water column, in some places as high as several kilometers. In this world, not all forests are tethered to the ground. Flowing with the currents, seeking sunlight, they hover near the surface, taking in nutrients and carbon dioxide and producing half the oxygen we need to breath.

Then imagine machines reaching down from above, harvesting everything they can, in some cases, just to be used to feed fish penned in fish farms. This industrial scale fishing and the resultant loss of biomass has interfered with the natural carbon cycle.

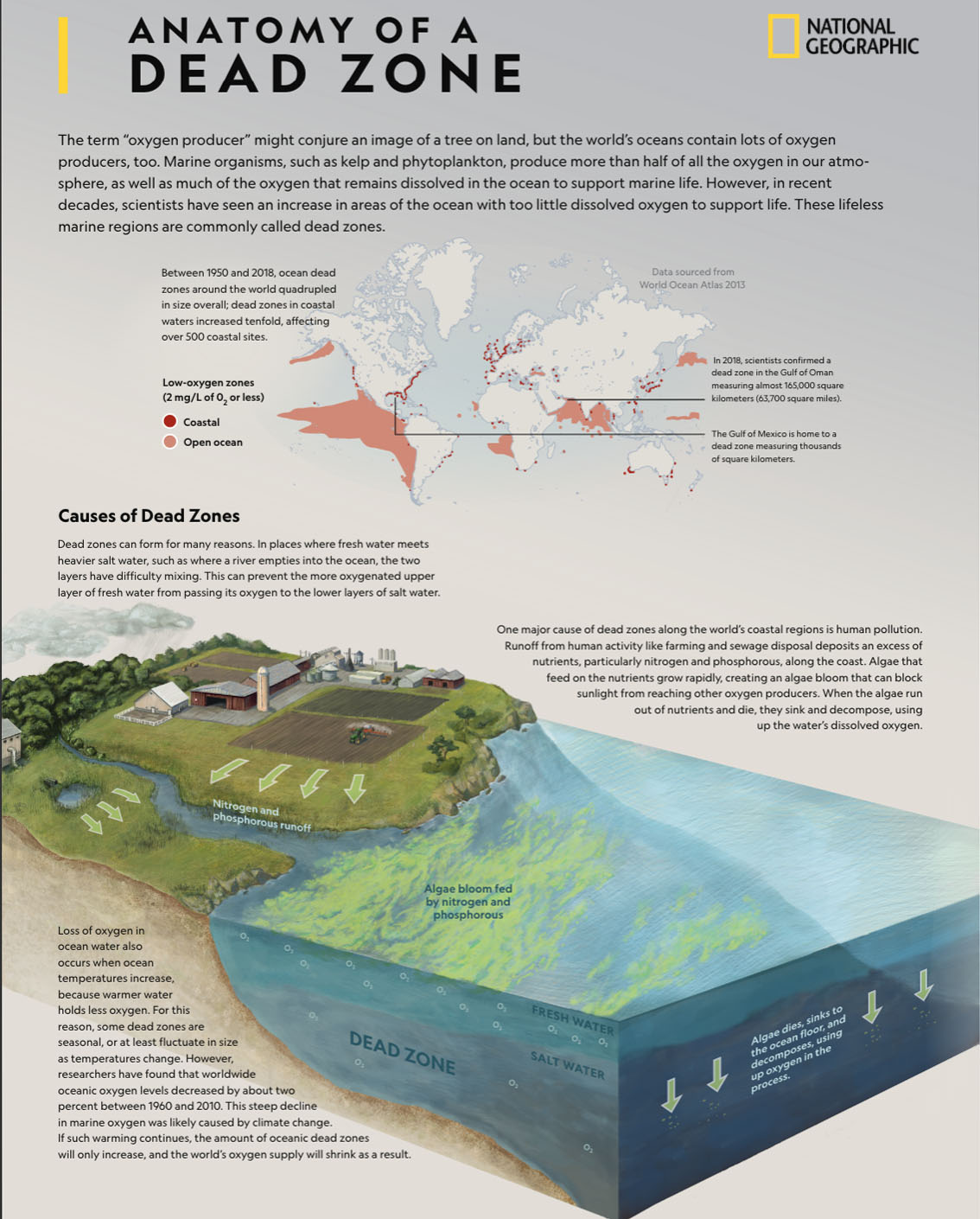

But in some case, bottom trawling aims to harvest just one or two species like the long-lived orange roughy—a mainstay of our fish ‘n chips in spite of it having some of the highest mercury content of any fish on the planet. The machine trawlers decimate everything in their paths, bulldozing and tearing apart the floors of the ocean, destroying reefs that took centuries to grow. The CO2 stored safely in the seabed is released, joining the 25-30% excess CO2 the oceans have already swallowed from the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution. This ‘double whammy’ now makes the water even more acidic. The few creatures left living in the upper reaches of the water column that survived the initial destruction soon die, robbed of crucial nutrients that they once exchanged with the bottom dwellers. The dead fall to the ocean floor. But now, with nothing left to recycle their nutrients, their decay turns hypoxic—a place devoid of oxygen. Nothing can live there anymore.

These are the ‘dead zones’. And they grow larger every year. This is not science fiction. This is our ocean (Fig. 1).

Along the coasts, the great living structures than once stored so much blue carbon—reefs, kelp, mangrove forests and seagrasses—are also decimated. Some of this destruction is to make way for massive coastal developments: harbours, fish farms, marinas, and multi-million dollar resorts. Others because of a combination of less visible but equally devastating marine heatwaves, which have doubled because of climate change, and increasingly acidic oceanic waters.

The solutions: Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

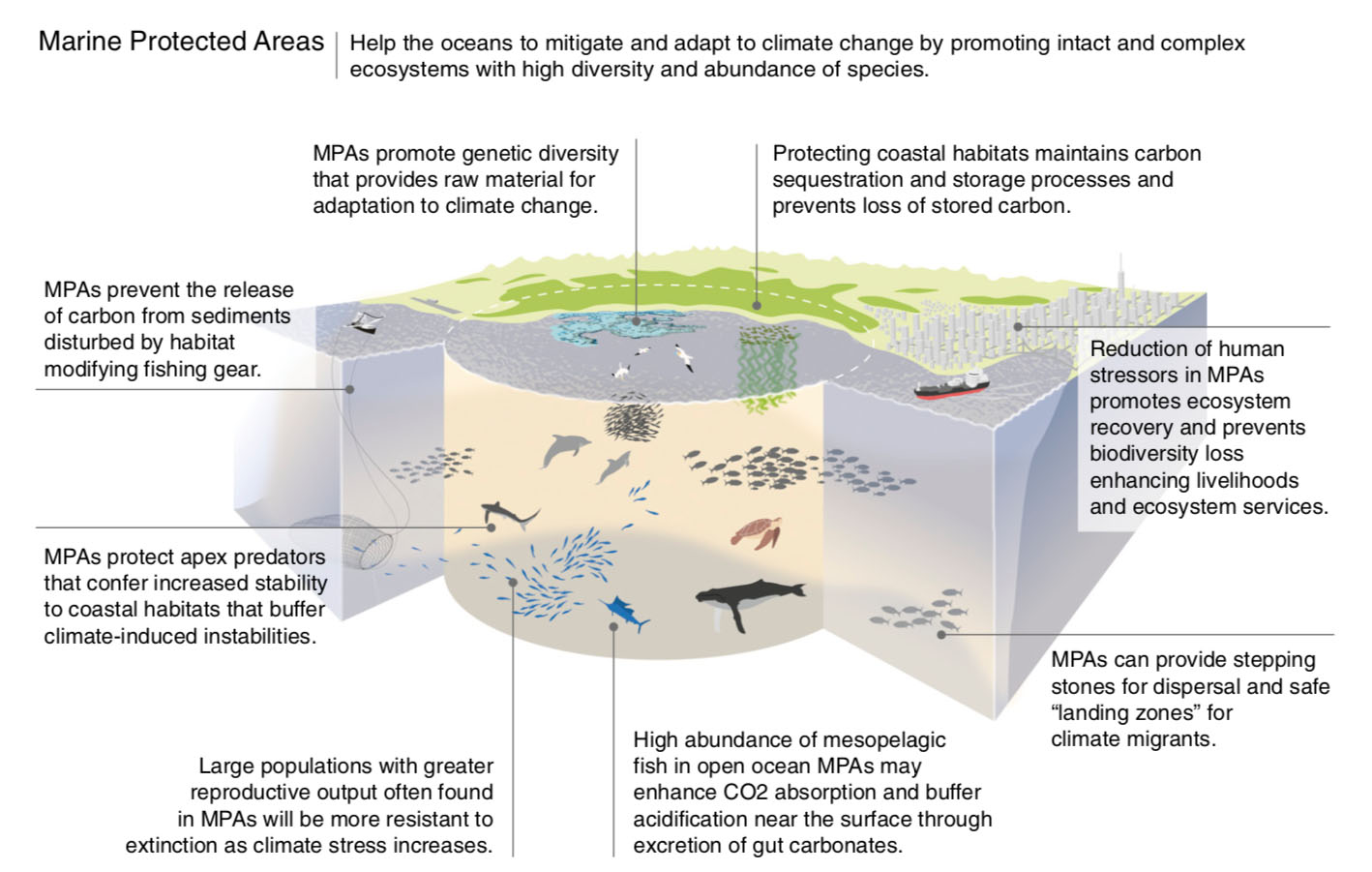

Protecting the oceans isn’t just about protecting fish stock. Without blue carbon we face an existential crisis—literally a threat to our existence. But as former NOAA director Jane Lubchenco says, it’s time to stop thinking of the ocean as a victim of climate change and start thinking of it as a powerful part of the solution (Fig. 2).

“Marine reserves are a viable low-tech, cost-effective adaptation strategy that would yield multiple cobenefits from local to global scales, improving the outlook for the environment and people into the future.” – Roberts et al 2017

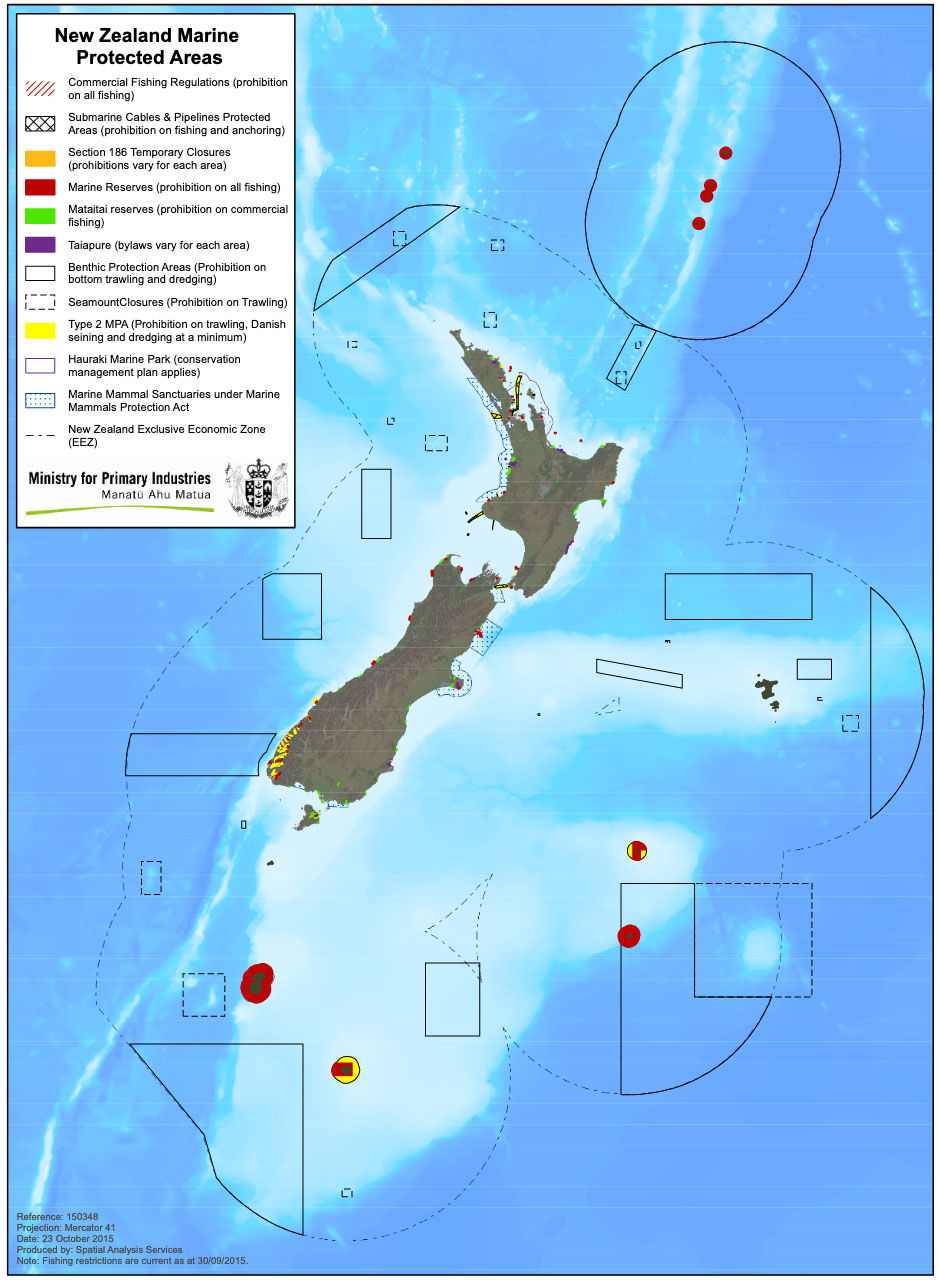

When we think of the unique plants and animals that inhabit Aotearo, we tend to think of kiwis and kakapo, weta and ferns. But, of the 65,000 species unique to New Zealand, ~80% are found in the ocean we claim as our economic zone. And yet, less than 1% of our marine and coastal biodiversity is fully protected compared with over 30% of our land (Fig. 3).

In the past, MPAs were created primarily to provide the foundation for sustainable fisheries. By not fishing in these areas, fish stocks not only replenish quickly, they soon spill over into areas outside the protected zones.

Providing seafood is just one part of the story. Oceanic currents play a critical role in our weather. We also need their blue carbon capabilities to draw excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. We need coastal oceanic ecosystems like reefs, mangroves, and sea-grasses to act as shock absorbers, helping to protect coastal lands from rising sea levels. So we need to protect more than just fish. We need to protect their homes so that they can protect ours.

“Sustainable Development Goal 14 of the United Nations aims to “conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.

“Achieving this goal will require rebuilding the marine life-support systems that deliver the many benefits that society receives from a healthy ocean. Here we document the recovery of marine populations, habitats and ecosystems following past conservation interventions.

“Recovery rates across studies suggest that substantial recovery of the abundance, structure and function of marine life could be achieved by 2050, if major pressures—including climate change—are mitigated. Rebuilding marine life represents a doable Grand Challenge for humanity, an ethical obligation and a smart economic objective to achieve a sustainable future.” – Duarte et al, 2021

Because these are long-lived predators, over their lifetime orange roughy consume tens of thousands of smaller fish, each of which has a percentage of the highly toxic

Because these are long-lived predators, over their lifetime orange roughy consume tens of thousands of smaller fish, each of which has a percentage of the highly toxic