The carbon budget: a moving target that politicians just moved beyond reach.

Bankrupting the Carbon Budget:

What tipping points mean for the carbon budget

In Bankrupting the Carbon Budget: Part I, tipping points were explained in Videos 1 and 2.

Others tipping points include wildfires in the Arctic and Australia. Together these released around 1Gt of CO2 in 2020. The devastation was so great in places that the conditions that led to the evolution of these ancient ecosystems no longer exist. ‘Zombie’ wildfires in boreal forests in Siberia and Canada and Alaska continue to burn peat underground over winter, re-igniting record-breaking forest fires in the summer of 2021.

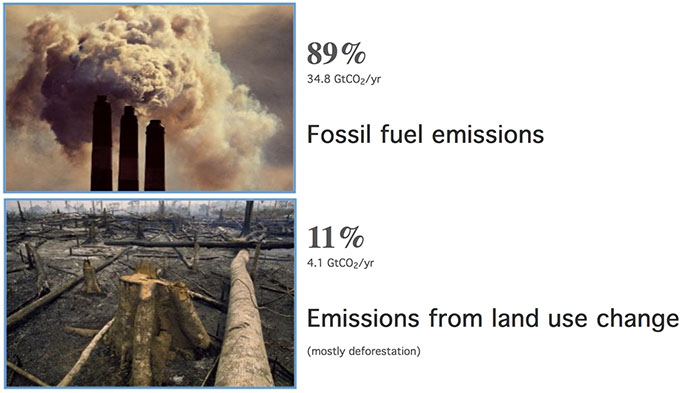

These forests, which make up large parts of the biosphere that once absorbed carbon and locked it away, are now releasing carbon to the atmosphere together with human-caused emissions. They have passed a tipping point; a point of no return. The countdown clock in Fig. 1 doesn’t include these emissions because the compound effects are so complex, they have yet to be included in Earth systems models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

But the atmosphere doesn’t care where these emissions originate. Nor how much nations—most notably New Zealand—or businesses cheat on their carbon accounting. The reality is that the carbon budget is a globally shared account. Governments think they know how much we have left to ‘spend’, but the burning forests and melting permafrost and methane clathrates are making CO2 withdrawals over which we have no control. All we know is that somewhere between warming of 1-2°C, some tipping points will be irreversible and warming will accelerate, causing even more tipping points to fall like dominoes.

A race against time

The relationship between the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere and warming is well-understood physics and chemistry. But there is a delay—a lag time of 10-20 years—between adding CO2 to the atmosphere and warming. So even if we switch off all emissions today, things will get hotter over the next two decades. It takes even longer for melting icecaps to raise sea levels, unless there’s an abrupt Meltwater Event (historically, these have raised sea levels as much as 4m/century).

The IPCC is banking our future existence on the lag time to literally buy us time to drawdown enough CO2 from the atmosphere and permanently store it back where it came from, with fingers crossed that will return the planet to a safe operating space of 350ppm.

The Plan: built-in assumptions

The crucial thing about The Plan is that it depends entirely on assumptions. The most important assumption is that carbon capture technologies will draw down and safely store CO2 underground before warming triggers irreversible tipping points. This assumption (otherwise known as magical thinking) is because there isn’t enough land on Earth to plant enough trees to offset emissions while still being able to grow food to feed an exploding global population:

The Plan by the numbers: 2019 – 2050

- Atmospheric concentration at the start of 2019: 408ppm

- Emit: no more than 400Gt of CO2 over the next 21 years; this would add around 23ppm to the atmosphere.

- Offset emissions: as some emissions are unavoidable, they must be 100% offset by drawing down the same amount of CO2 as emitted and storing it permanently underground or in natural ecosystems. Plantation forestry is by definition not permanent, so it shouldn’t be regarded as a permanent offset because the carbon in it is recycled back into the atmosphere.

- Draw down: an average 3.9Gt of CO2 every year (total 81.9Gt between 2019-2050) and store it underground and in natural ecosystems. In total, this would remove around 10.5ppm. Again, plantation forestry shouldn’t be regarded as a permanent drawdown.

- Together, The Plan means that atmospheric concentration as of January 2050 will be: 408ppm + 23ppm – 10.5pm = 420.5ppm.

- Limitations to offsetting and drawdown:

- The world’s terrestrial ecosystems can only hold between 40 and 100Gt, so by 2050, CO2 will need to be permanently stored elsewhere.

- Burning forests and melting permafrost and methane clathrates are emitting CO2 and methane. We don’t know how much, we have no control over it, but we do know this is eating into the existing carbon budget.

The Plan by the numbers: 2050 – 2100

- The planned atmospheric concentration at the start of 2050: 420.5ppm

- Emit: zero CO2

- Offset: As some emissions are unavoidable, they must be 100% offset by drawing down the same amount of CO2 as emitted and storing it permanently underground. By now, terrestrial ecosystems will be unable to store any more carbon.

- Draw down average 24Gt/year until 2100 (24Gt x 50 years = 1,250Gt or 72ppm) and store it…somewhere.

- Planned atmospheric concentration at the start of 2100: 420.5ppm – 72ppm = 348.5ppm.

- Limitations to offsetting and draw down:

- Burning forests and melting permafrost and methane clathrates will be emitting far more CO2 and methane, so the budget will likely need further revision.

The Plan: how are we doing so far? 2019 – 2021

- Atmospheric concentration at the start of 2019: 408ppm

- Atmospheric concentration at start of 2022: 418ppm, ie, we’re going to hit 420.5pm before 2024, not 2050.

- Emitted: 107Gt of CO2 (26.7% of the 21-year budget ‘spent’ in 3 years)

- Offset: A handful of the world’s largest carbon polluters are buying up most of the land available for afforestation/reforestation to offset their emissions, leaving no available land for others to offset theirs. This includes land needed to feed people. Many are investing in low value or ‘ghost’ forests such as palm oil plantations, because plants that grow faster earn far more money from carbon credits. Many corporations have no plans to ever become carbon neutral because they will pass the cost of cheap and often useless offsets onto customers. The New Zealand Government, which is using taxpayer dollars to subside the eye-watering carbon cost of agriculture (giving them a 95% discount on emissions), and Fonterra, our largest carbon polluter, also plan to buy carbon credits offshore because they’re cheaper.

- Draw down: In spite of all the reforestation and rewilding projects around the globe, terrestrial ecosystem destruction (land use change) exceeded reforestation and offsetting by approximately 10Gt (Fig. 2). A large chunk of these losses are from the Amazon, parts of which have become so dry that they can no longer support re-forestation, so they’re turning in savannahs or being used to grow palm oil, soya, and methane-emitting cows.

- Limitations to offsetting and drawdown:

- Oddities with emissions trading schemes not accounting for the value of carbon locked in established forests and their soils, has created perverse incentives: old-growth and naturally regenerating forests are being cut down and/or burned so they can be replaced by fast growing monoculture crops like pine forests that earn more from carbon credits (if they survive wildfires and rapidly rising temperatures). And COP26 did nothing to prevent this from happening into the future (scroll down).

- The only company extracting CO2 and permanently storing it underground (versus selling it as fuel) is in Iceland. In September 2021, Climeworks’ operations scaled up. It now draws down and stores 4,000 tonnes CO2/year. To scale up to 3.9Gt/year (‘The Plan’) would require building and deploying 9.5 million additional fully operating plants of the same size. To scale up to 24Gt/year from 2050 onward would require 58.5 million additional fully operational plants of the same size. And then there’s this:

- Oddities with emissions trading schemes not accounting for the value of carbon locked in established forests and their soils, has created perverse incentives: old-growth and naturally regenerating forests are being cut down and/or burned so they can be replaced by fast growing monoculture crops like pine forests that earn more from carbon credits (if they survive wildfires and rapidly rising temperatures). And COP26 did nothing to prevent this from happening into the future (scroll down).

“No artificial machines that are even in the design stage will also clean our air, clean our water, provide habitat for wildlife and all the other useful features of trees.” – Sophie Bertazzo, Senior editor, Conservation International

COP26: bankrupting the carbon budget

COP26: The oceans

As Bonnie Waring said in the quote above:

“If we absolutely maximised the amount of vegetation all land on Earth could hold…”

The oddity in The Plan is that it largely ignores 70% of the surface of the planet that’s not land: the oceans, or more specifically the blue carbon in them. For the first time, the capability of the oceans to rapidly draw down and permanently store vast quantities of CO2 was finally addressed at COP26.

New Zealand has an exclusive oceanic economic zone 14 times larger than our land area. Why isn’t the government (and heavy carbon polluters) using that incredible capacity to invest far more in locally produced blue carbon? Fed by the sun, with no need for irrigation or agricultural chemicals, some species can grow up to 1m/day, drawing down as much as five times more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than rainforests, and permanently sequestering if not harvested and instead, cut and dropped into deep ocean.

Watch this (deep blue) space.

More information

- COP26: The final draft

- Glasgow’s 2030 credibility gap: net zero’s lip service to climate action: Climate Action Tracker

- Detailed analyses of each component of COP26: Carbon Brief (scroll down the page a bit to see the links to each section)