With the failure of a global plastics treaty—oil-rich nations and the petrochemical industry putting up the strongest opposition—the following article should give food for thought, especially as every mouthful of seafood contains microplastics.

We’ve all seen the impact of our plastic addiction. It’s hard to miss the devastating images of whales and sea birds that have died with their stomachs full of solidified fossil fuels. The recent discovery of a plastic bag in the Mariana Trench, at over 10,000 metres below sea level, reminds us of the depth of our problem. Now, the breadth is increasing too. New research suggests that chemicals leaching from the bags and bottles that pepper our seas are harming tiny marine organisms that are central to sustained human existence.

Once plastic waste is out in the open, waves, wind and sunlight cause it to break down into smaller pieces. This fragmentation process releases chemical additives, originally added to imbue useful qualities such as rigidity, flexibility, resistance to flames or bacteria, or a simple splash of colour. Research has shown that the presence of these chemicals in fresh water and drinking water can have grave effects, ranging from reduced reproduction rates and egg hatching in fish, to hormone imbalances, reduced fertility or infertility, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer in humans.

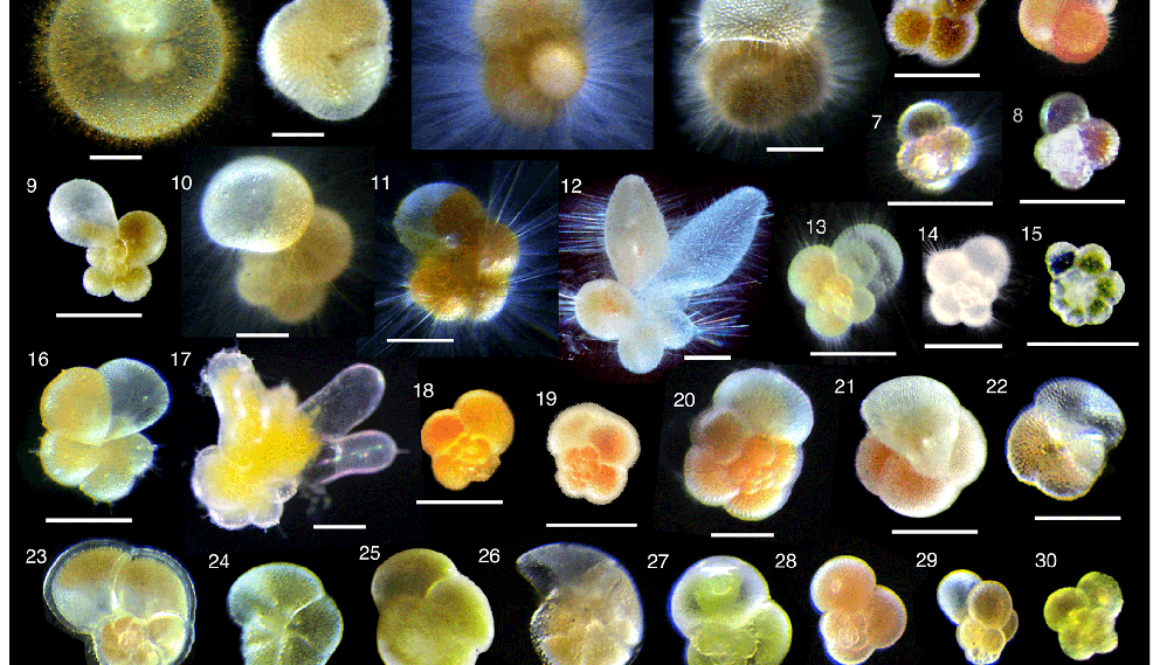

But very little research has looked at how these additives might affect life in our oceans. To find out, researchers at Macquarie University prepared seawater contaminated with differing concentrations of chemicals leached from plastic bags and PVC, two of the most common plastics in the world. They then measured how living in such water affected the most abundant photosynthesising organism on Earth – Prochlorococcus. As well as being a critical foundation of the oceanic food chain, they produce 10% of the world’s oxygen.

The results indicate that the scale and potential impacts of plastic pollution may be far greater than most of us had imagined. They showed that the chemical-contaminated seawater severely reduced the bacteria’s rate of growth and oxygen production. In most cases, bacteria populations actually declined.

What can be done?

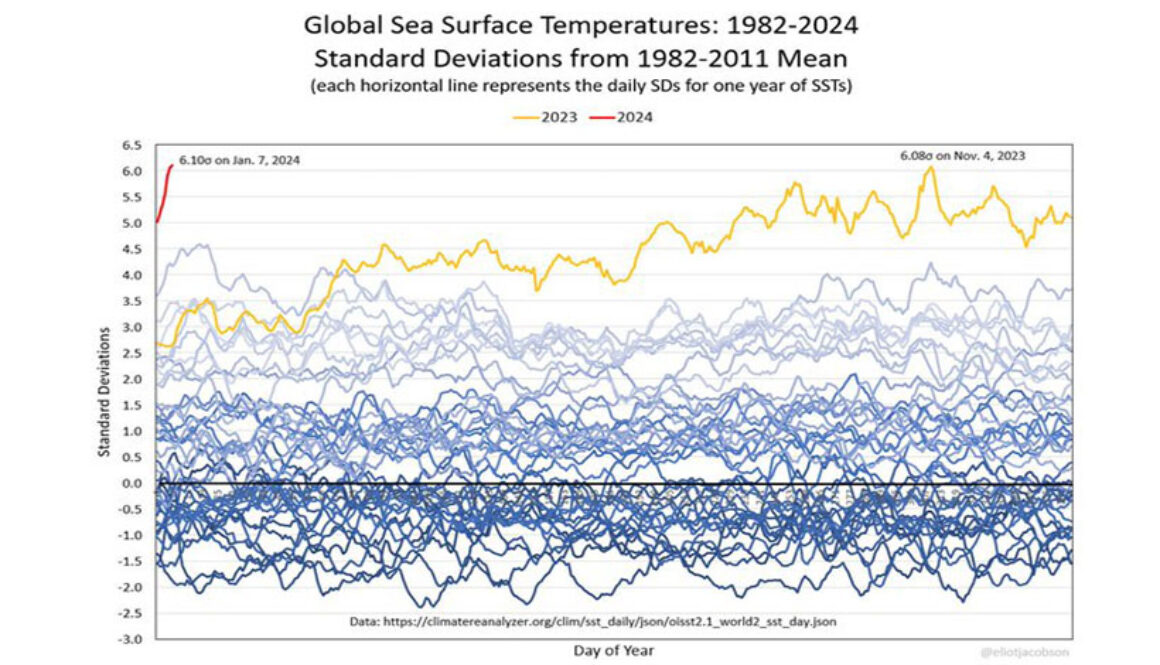

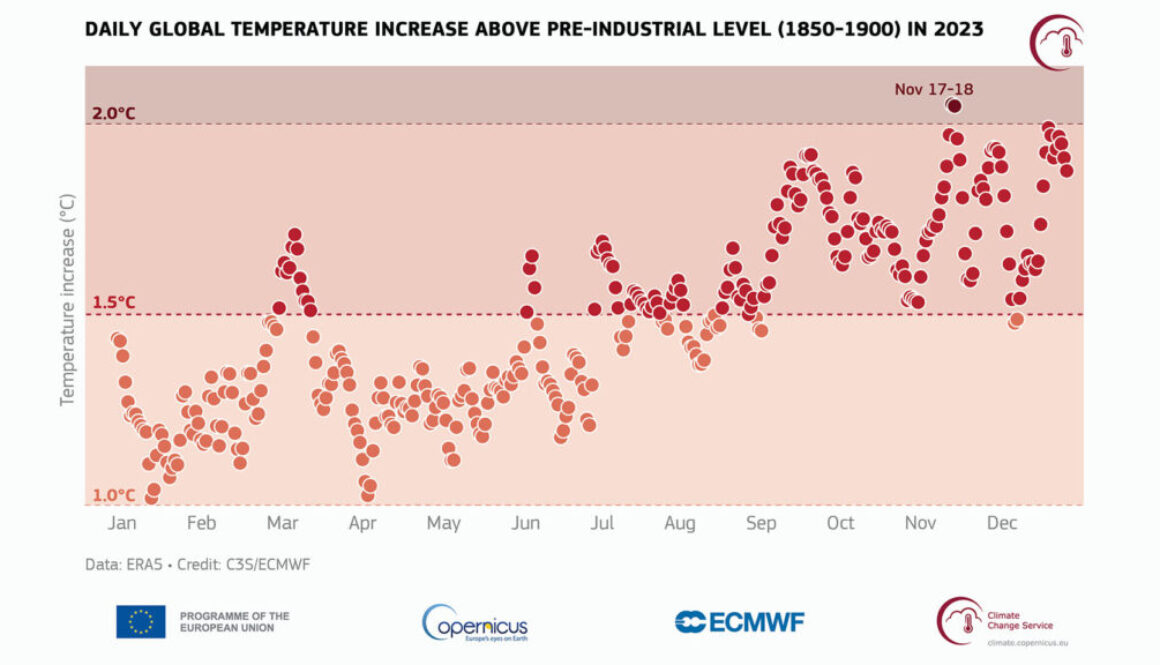

Given the importance of oxygen levels to the rate of global heating, and the vital role these phytoplankton play in ensuring thriving marine ecosystems, it is essential that we now conduct research outside of the laboratory into the effects of plastic additives on bacteria in the open seas. In the meantime, we need to take active steps to reduce the risks of chemical plastic pollution.

The clear first step is to reduce the amount of plastic entering the ocean. Recent EU and UK bans on single-use plastics are a start, but much more radical policies are needed now to reduce the role plastic plays in our lives as well as to stop the plastic we do use being released into waterways and dramatically improve appallingly low recycling rates.

At an international level, we must make addressing the waste produced by the fishing industry a priority. Broken fishing nets alone account for almost half of the plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch – and lost or discarded fishing gear accounts for one-third of the plastic litter in European seas. EU incentives announced in 2019 to tackle this waste do not go far enough.

Legislation is also urgently needed to limit the industrial use of harmful chemical additives to a level that is absolutely necessary. As an example, bisphenol A, found in myriad products ranging from receipt paper to rubber ducks, is now listed as a “substance of very high concern” due to its hormone-disrupting effects. But as yet the few existing laws regulating the chemical do not cover the majority of industrial use. This needs to change – as quickly as possible.

Of course, even if we can completely stop new chemicals from reaching the oceans, we will still have a legacy of plastic and associated chemical pollution to deal with. At the moment, we have no idea whether we’ve already done irreversible damage, or if marine ecosystems are resilient to current levels of plastic pollution in the open oceans. But the health of our oceans is not something we can risk. So, in addition to physical removal schemes such as The Ocean Clean Up, we need to invest in chemical removal technologies as well.

In salty ocean environments, such technologies are under-researched. We are currently in the early stages of developing a floating device that uses a small electric circuit to transform BPA into easily retrievable solid matter, but our work alone is not enough. Scientists and governments need to ramp up their efforts to both understand and eliminate the problem of chemical contamination of our oceans, before it’s too late.

While ocean bacteria may seem far removed from our daily lives, we are dependent on these tiny organisms to maintain the balance of our ecosystems. We ignore their plight at our peril.![]()