wildfire

After a series of natural disasters – from the Canterbury earthquakes to Cyclone Gabrielle – real doubt hangs over the insurance options available to some New Zealand homeowners.

Increasingly, homes in certain areas are becoming uninsurable – or difficult to insure, at least. Insurers have decided the risk is too high to make covering it financially viable, leaving affected homeowners vulnerable.

The question of how insurers can continue to offer policies – all the while managing the growing risk from natural disasters – is becoming hard to ignore.

Insurers will have to explore alternative models and innovate if New Zealand is to adapt to future change.

Cautious insurers

There’s no general requirement in New Zealand that insurers cover anyone’s home, or that anyone’s home actually be insured.

Body-corporate groups are one exception. They must insure the units they manage. Mortgage lenders can also require borrowers to take out home insurance as part of their lending conditions.

When homeowners do get insurance, the risk of certain losses from natural disasters is automatically covered by the Natural Hazards Commission (previously known as the Earthquake Commission).

Even if a home insurance policy were to contain wording that, on the face of it, excluded this public natural-disaster cover, the law would treat the cover as included. At the same time, payouts are only managed by insurers, not financed by them.

The Canterbury earthquakes cost insurers NZ$21 billion and the Natural Hazards Commission $10 billion. And the risk of natural disasters more generally may be making insurers too cautious. They’re increasingly pulling out of areas they consider “high risk”.

That said, there are changes on the horizon. From mid-2025, insurers will have a general duty to “treat consumers fairly”. The Financial Markets Authority – the body responsible for enforcing financial-markets law – may potentially regard refusing home insurance to any consumer as a breach of the duty.

In other words, the Financial Markets Authority may end up forcing insurers to cover most of the country’s homes.

New insurance options

Future-proofing home insurance options will depend on the public and private sectors working together.

Many of the potential solutions are specific to how insurers take risk on. An insurer may decrease your premiums as an incentive for you to “disaster-proof” your home. If you don’t, the insurer may increase your premiums and limit its payouts to you, with individualised excesses or caps.

The insurer may even offer “parametric” insurance, which pays out less than traditional insurance, but faster.

For example, imagine a home insurance policy that covers any earthquake having its epicentre within 500 kilometres of your home, and measuring magnitude six or higher.

A traditional policy would pay out based on how much loss was caused (according to a loss adjuster). A parametric policy would simply pay out a small, pre‑agreed sum, based on the fact the earthquake occurred at all.

A parametric policy wouldn’t require you to prove any actual “loss” – beyond the inconvenience of having your home in the disaster zone.

While parametric insurance is relatively new worldwide, it’s an efficient solution for managing the risk of natural-disaster damage.

Reinsurance, co-insurance and ‘cat bonds’

An insurer may also transfer risk to one or more other insurance businesses – such as a “reinsurer”. If the insurer has to make a payout to you for a claim, the reinsurer then has to make a payout to the insurer for a portion of it.

The insurer may even “co‑insure” the risk. Co‑insurance is where two or more insurers cover different portions of the same risk. So, if you have your home co‑insured, you will have two or more insurers, each responsible for a portion of any claim.

Then there is the potential to transfer insured risk to entities that aren’t even insurance businesses. In some countries (such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands and Ireland), the insurer can turn the risk into a “catastrophe bond” (also known as a “cat bond”).

Under a cat bond, the insurer arranges for expert investors to lend it capital in return for interest on the loans. The insurer eventually repays the capital, unless there is a specific natural disaster. In that case, the insurer keeps the capital, enabling it to pay out to the affected customers.

The insurer may even use the cat bond to create a “virtuous cycle”. More specifically, the insurer may reinvest the capital in “a project that reduces or prevents loss from the insured climate-related risk” (such as flooding).

Disaster-proofing the insurance industry

Key to improving the situation will be the public and private sectors working together to make climate-related disasters less frequent – and less serious when they occur.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has advised on how the sectors could minimise climate-related risk. But they also have similar progress to make to minimise the risk of natural-disaster damage more generally, particularly from earthquakes.

It is important to build homes that are better disaster-proofed. And it is also important to address a major problem that many people don’t necessarily view as related to insurance – the cost of housing.

If New Zealanders wishing to own their homes didn’t have to invest as much of their money in housing as they do, the risk of damage to housing might be of less concern. Natural disaster wouldn’t have to mean financial disaster as much as it does today.

In the meantime, innovative insurance options will become more and more necessary.![]()

Christopher Whitehead, Lecturer in Law, Auckland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

_________________________________________________________________________________

It feels like we are getting used to the Earth being on fire. Recently, more than 70 wildfires burned simultaneously in Greece. In early 2024, Chile suffered its worst wildfire season in history, with more than 130 people killed. Last year, Canada’s record-breaking wildfires burned from March to November and, in August, flames devastated the island of Maui, in Hawaii. And the list goes on and on.

Watching the news, it certainly feels like catastrophic extreme wildfires are happening more often, and unfortunately this feeling has now been confirmed as correct. A new study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution shows that the number and intensity of the most extreme wildfires on Earth have doubled over the past two decades.

The authors of the new study, researchers at the University of Tasmania, first calculated the energy released by different fires over 21 years from 2003 to 2023. They did this by using a satellite-based sensor which can identify heat from fires, measuring the energy released as “fire radiative power”.

The researchers identified a total of 30 million fires (technically 30 million “fire events”, which can include some clusters of fires grouped together). They then selected the top 2,913 with the most energy released, that is, the 0.01% “most extreme” wildfires. Their work shows that these extreme wildfires are becoming more frequent, with their number doubling over the past two decades. Since 2017, the Earth has experienced the six years with the highest number of extreme wildfires (all years except 2022).

Importantly, these extreme wildfires are also becoming even more intense. Those classified as extreme in recent years released twice the energy of those classified as extreme at the start of the studied period.

These findings align with other recent evidence that wildfires are worsening. For instance, the area of forest burned every year is slightly increasing, leading to a corresponding rise in forest carbon emissions. (The total land area burned each year is actually decreasing, due to a decrease in grassland and cropland fires, but these fires are lower intensity and emit less carbon than forest fires).

Burn severity – an indicator of how badly a fire damages the ecosystem – is also worsening in many regions, and the percentage of burned land affected by high severity burning is increasing globally as well.

Although the global outlook is overall not good, there are striking differences among regions. The new study identifies boreal forests of the far north and temperate conifer forests (blue and light green in the above map) as the critical types of ecosystem driving the global increase in extreme wildfires. They have the higher number of extreme fires relative to their extent, and show the most dramatic worsening over time, while also seeing an increase in total burned area and percentage burned at high severity. The confluence of these three trends is particularly pervasive in eastern Siberia, and the western US and Canada.

What turns a fire into a catastrophe

Nonetheless, many other regions are also susceptible to fires becoming more consequential, as what turns a fire into a catastrophe depends not only on fire trends but also on the environmental, social and economic context.

For instance, in temperate broadleaf forests around the Mediterranean, there has not been a big change in fire activity and behaviour. But the growing number of houses built in and around wild vegetation in fire-prone areas is a clear example of an action that increases human risk and can lead to catastrophe.

The doubling in extreme wildfires adds to a complex picture of fire patterns and trends. This new evidence underscores the urgency of addressing the root causes behind worsening wildfire activity, such as land cover changes, forest policies and management, and, of course, climate change. This will better prepare us for these extreme fires, which are near-impossible to combat using traditional firefighting methods.![]()

Víctor Fernández García, Chargé de recherche at the University of Lausanne, Université de Lausanne and Cristina Santín, Honorary Associate Professor, Biosciences, Swansea University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

First published 19 September 2023, in Environmental Research Letters 18; reproduced here under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence

Authors:

-

Giorgia Di Capua:Magdeburg-Stendal University of Applied Sciences, 39114 Magdeburg, Germany

-

Stefan Rahmstorf: Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), Member of the Leibniz Association, PO Box 6012 03, D-14412 Potsdam, Germany | E-mail: dicapua@pik-potsdam.de

Abstract

Extreme weather events are rising at a pace which exceeds expectations based on thermodynamic arguments only, changing the way we perceive our climate system and climate change issues. Every year, heatwaves, floods and wildfires, bring death and devastation worldwide, increasing the evidence about the role of anthropogenic climate change in the increase of extremes. In this viewpoint article, we summarize some of the most recent extremes and put them in the context of the most recent research on atmospheric and climate sciences, especially focusing on changes in thermodynamics and dynamics of the atmosphere. While some changes in extremes are to be expected and are clearly attributable to rising greenhouse gas emissions, other seem counterintuitive, highlighting the need for further research in the field. In this context, research on changes in atmospheric dynamics plays a crucial role in explaining some of these extremes and more needs to be done to improve our understanding of the physical mechanisms involved.

_______________________________________

A rise in weather extremes is probably the most severe early impact of rising global temperatures. Extreme weather events have a high impact on both human activities and natural ecosystems. In recent decades the world has seen an increase in heatwaves, droughts, flooding events and fire weather conditions, as expected in a warming climate. 2022 has been no exception, with record-breaking high temperatures registered across large portions of Western Europe, China and Pakistan (Hausfather 2023). In Pakistan, extreme monsoon rains and Himalayan glaciers melting away in a heat wave have flooded approximately 85 000 km2 (USAID 2022), killing more than 1700 people and causing $15 billion of damage (World Bank), while the Horn of Africa has seen an unprecedented drought that has pushed more than three million people into emergency food insecurity (NASA Earth Observatory 2022). Many of these events have been made more likely by anthropogenic warming and represent a serious threat to human society, with effects ranging from health and mortal- ity to economy and national security issues.

Even for lay persons it will be obvious that heat extremes will increase in a warming world. But it may be unexpected by how much: monthly heat extremes

that were three standard deviations above average during the baseline period 1951–1980 have already increased over 90-fold in frequency over the global land area, while the formerly near-unprecedented 4-sigma events have increased 1000-fold to affect 3% of the land area in any given month, data show (Robinson et al 2021). July 2023 was the hot- test month on record on Earth by a large margin (Copernicus 2023a), and likely the hottest for at least 10 000 years. Marine heatwaves have also doubled in the last few decades, and they are expected to see a 23-fold increase under a 2 ◦C warming scenario (Frölicher et al 2018)—the off-the charts sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic in summer 2023 are a stern foretaste of this (Copernicus 2023b), while in Florida the marine heatwave caused wide spread bleaching turning into one of the worst events in the region on record (Dennis et al 2023).

Part of this is as expected simply by shifting a Gaussian normal distribution towards warmer values; the more extreme an event, the larger is the factor by which its likelihood increases. However, explaining the full extent of the global increase in extreme heat requires additional, dynamical effects (which we will discuss below).

And heat—especially lasting heat—is a silent killer. The death toll of the 2003 European heat wave has been estimated as ∼70 000 (Robine et al 2008), with a mortality peak in France higher than dur- ing any Covid19 wave (Ferrer and Breteau 2020). A first estimate for summer 2022 came in at ∼62 000 (Ballester et al 2023), when even in Britain temperatures soared above 40◦C for the first time in history. Temperature-related excess mortality is expected to increase with unmitigated global warming, even when accounting for a decrease in cold-related deaths (Gasparrini et al 2017).

Since early 2012, the fingerprint of climate change can be detected in any single day in the observed record. There are no more days on Earth where global weather is not significantly different from what it would be without human influence—on nearly all days even when just considering the weather pat- terns without the increase in global-mean temperature (Sippel et al 2020). Observations show that nearly the entire Earth surface has warmed since the late 19th century (except for the prominent ‘warming hole’ south of Greenland and Iceland, Rahmstorf et al 2015) and the annual global mean temperature has increased by 1.2◦C since the late 19th Century (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2021). The intensity and speed of warming differ by region, with land areas warming twice as much as the ocean surface since 1970 (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2021). Warming is more prominent in the Arctic, Eastern Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, East Asia and western North America. Key heatwave characteristics, such as frequency, duration and cumulative heat (i.e. the heat produced by heatwaves days inside a season), show increasing trends since 1950 at global scale, with stronger trends in tropical and northern latitudes. Trends for these key variables have been accelerating in the past few decades (Perkins-Kirkpatrick and Lewis 2020). Summer 2023 was no exception, with record breaking temperature recorded in Southeastern US, China, Spain, Morocco, rendered more likely by current climate change (Zachariah et al 2023).

While the world-wide rise in heat extremes is easily understood given the rise in global mean temperature, mean global rainfall and extreme precipitation trends depict a more complex relationship. Global rainfall is expected to increase as evaporation from warmer oceans increases. Indeed, the IPCC AR6 WGI (2021) reports an increase in globally averaged land precipitation since 1950, though with medium confidence given the large variability and spatial heterogeneity of precipitation. However, extreme rainfall events have shown a steep increase in the last few decades (especially in tropical regions), with 1 in 4 record breaking rainfall events being attributable to climate change (Robinson et al 2021). In August 2023, the region surrounding Beijing was hit by a severe flood event which saw the highest rainfall record of

the last 140 years (744.8 mm in less the 4 d) (Hawkins 2023) Perhaps counterintuitively, some areas even show opposite trends in mean precipitation rates and extreme rainfall events. One such example is the Indian summer monsoon system, which shows a slight decrease in its mean seasonal precipitation rates together with a three-fold increase in extreme rainfall events during the 1950–2015 period (Roxy et al 2017). Therefore, when considering the effect of climate change on extremes, it is not enough to look at trends in mean values.

Another example of that is that despite the global-mean (and often also local) rainfall increase, the frequency and severity of droughts has also increased in some regions, for a number of reasons. One overall reason is that with approximately constant relative humidity, air will contain (and at some point rain out) 7% more moisture per degree of warming, while the resupply of water via evaporation increases only by 2%–3% per degree (Allan et al 2020). The additional evaporation and rain- fall tends to end up in heavy rain rather than alleviating drought: Half of it comes down in the wet- test 6 d each year (Pendergrass and Knutti 2018), and the heaviest rainfall events increase most strongly (Fischer and Knutti 2015). Also, increasing agricultural and ecological droughts (i.e. loss of soil moisture and drying vegetation) can be caused not just by declining precipitation but also by rising temperatures causing faster evapotranspiration. In different regions, either of these effects can be the more important one (Cook et al 2018). Major droughts can also result from natural climate variability and are rare events (compared to the length of available observational data). Thus, studying their trend and, more importantly, attributing them to anthropogenic global warming is not an easy task (Cook et al 2018). Several regions in the world have shown an increase in drought risk, such as Western North America, the Mediterranean, East Southern Africa, East Asia and South Australia, at least partly attributable to anthropogenic warming, with the Mediterranean and the North-Western North America showing the highest confidence (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2021).

In the past decade, wildfire activity has produced some new extreme fires that are unprecedented regarding propagation speed, intensity, location, timing and burnt area (Descals et al 2022, Senande- Rivera et al 2022). For example, the Australian ‘Black Summer’ wildfire disaster in 2019/2020 fol- lowed Australia’s hottest and driest year on record, burned more than half of the habitat for over 1600 native species and directly caused 33 human deaths and almost 450 more from smoke inhalation (Himbrechts 2021). An increase in extreme fire weather conditions can already be detected at global scale, although trend magnitude and spatial patterns vary at regional scale (Jain et al 2022). Globally, anthropogenic global warming is projected to cause unprecedented increases in extreme fire weather risk in the 21st century (Touma et al 2021). Model experiments estimate that anthropogenic induced changes in fire weather indices have already emerged from natural variability for 22% of the burnable land area globally by 2019, while by the mid twenty-first century the emergence will reach 30%–60% (Abatzoglou et al 2019). Meanwhile, in August 2023, Hawaii has experienced its worst wildfire on record, and one of the worst in US history, where dry conditions and hurricane-force winds fueled the flames bringing utter devastation to the town of Lahaina, killing at least 93 people and thus surpassing the death toll of the Camp fire in California in 2018 (Gabbat and Anguiano 2023).

While warm extremes are to be expected due to anthropogenic global warming, cold extreme are projected to decrease in this century. Nevertheless, despite the general increase in global surface temperatures, a few regions show a cooling trend in the historical record. One such example is central Siberia, which features a cooling trend during boreal winter (Inoue et al 2012). While both natural variability and anthropogenic forcing are debated as causes of this trend (Inoue et al 2012), the cooling trend is mainly associated with an increase in cold extremes over the region. Cold air outbreaks in central Siberia and North America have been shown to result from sudden stratospheric warming events and a disruption of the stratospheric Polar vortex (Kretschmer et al 2018).

Detecting climate change signals can be challenging depending on the region and the variable selected, and attributing trends in temperature or precipitation fields to changes in thermodynamic or dynamic features of the atmosphere represent an even greater challenge (Shepherd 2014). In general, the largest portion of the change is to be attributed to thermodynamic effects. However, dynamic changes can further exacerbate thermodynamic driven changes and atmosphere dynamics and changes in weather patterns play an important role at regional scale (Rousi et al 2022). Amplified Rossby waves with preferred phase position, in particular waves with wave numbers 5 and 7, can lead to concurrent heatwaves (and crop failures) in the mid-latitudes (Kornhuber et al 2020), raising concerns about future food security. Arctic amplification, despite being more prominent in winter than summer, may also affect westerly winds, storm tracks and wave-guides in the mid-latitudes (Coumou et al 2018). Analyzing the ability of models to reproduce amplified waves 5 and 7 shows that even a small bias in upper tropospheric circulation features can have a strong impact on surface temperature and rainfall patterns (Luo et al 2022), highlighting that it is difficult for global climate models to simulate all mechanisms that contribute to making weather more extreme.

Europe has emerged as a hot-spot of heat extremes: it has seen a stronger increase in summer heat than other regions in the northern mid-latitudes. This enhanced warming has been related to dynamical changes such as an increase of double jet patterns, which could explain all of the additional rise in heat waves beyond what is expected simply by thermodynamics (Rousi et al 2022). Both observation and model experiment support the hypothesis that shrinking Arctic sea ice and reduced snow cover over northern Eurasia in spring can also contribute to increased blocking over Europe and consequent frequency of heatwaves (Zhang et al 2020). Sea surface temperature anomalies (in particular the northern Atlantic ‘warming hole’ mentioned earlier) can also reinforce heatwaves in central Europe, such as in 2015 (Duchez et al 2015).

In summary, it is now clear that global warming is already greatly increasing the number and intensity of many types of weather extremes, as has been predicted by climate science for decades. Much of this is due to thermodynamics. With that we mean that the atmosphere is warmer, which means it holds more energy and water to power extreme weather. The ocean is also warmer and can provide more energy and moisture as fuel to tropical cyclones. However, increasingly the attention of researchers has turned to dynamic effects. With that we refer to changes in circulation and stability of atmosphere and ocean. It includes changes to the jet stream, polar vortex, atmospheric planetary waves or to the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation.

Obtaining robust conclusions about changes in weather extremes requires long time series, given that extreme events are by definition rare events and are not easy to model. Nevertheless, the signal of climate change has now clearly emerged from the noise for many types of extremes. Disentangling the dynamic mechanisms is harder again and represents a current frontline of research. Driving forces behind dynamic changes are often regionally diverse temperature changes, such as Arctic amplification, enhanced land warming and sea surface temperature anomalies. Many facets of the dynamic mechanisms are still being debated in the scientific literature. Even if not everything is fully understood, researchers and journalists should not be shy to use every opportunity to educate the public about the fact that human-caused global warming is making weather extremes worse, already causing serious harm to many millions of people.

Even once global warming is stopped, we will see unprecedented extremes for a long time to come. Just think of a former once-in-5000 year event which at 1.5◦C warming may have become a once-in-50 year event. Thus, it will take many decades until we have seen all the possible extreme events a 1.5◦C warmer world has in store for us.

References

Abatzoglou J T, Williams A P and Barbero R 2019 Global emergence of anthropogenic climate change in fire weather indices Geophys. Res. Lett. 46 326–36

Allan R P et al 2020 Advances in understanding large-scale responses of the water cycle to climate change Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1472 49–75

Ballester J, Quijal-zamorano M, Fernando R, Turrubiates M, Pegenaute F, Herrmann F R, Robine J M and Basagan ̃a X 2023 Heat-related mortality in Europe during the summer of 2022 Nat. Med. 29 1857–66

Cook B I, Mankin J S and Anchukaitis K J 2018 Climate change and drought: from past to future Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4 164–79

Copernicus 2023a July 2023 sees multiple global temperature records broken Copernicus (available at: https://climate. copernicus.eu/july-2023-sees-multiple-global-temperature- records-broken)

Copernicus 2023b Record-breaking North Atlantic Ocean temperatures contribute to extreme marine heatwaves Copernicus Online (available at: https://climate.copernicus. eu/record-breaking-north-atlantic-ocean-temperatures- contribute-extreme-marine-heatwaves)

Coumou D, Di Capua G, Vavrus S, Wang L and Wang S 2018 The influence of Arctic amplification on mid-latitude summer circulation Nat. Commun. 9 2959

Dennis B, Ajasa A and Mooney C 2023 As Florida ocean temperatures soar, a race to salvage imperiled corals (Washington Post) (available at: www.washingtonpost.com/ climate-environment/2023/07/26/florida-coral-reef-ocean- temperatures-heat/)

Descals A, Gaveau D L A, Verger A, Sheil D, Naito D and Pen ̃uelas J 2022 Unprecedented fire activity above the Arctic circle linked to rising temperatures Science 378 532–7

Duchez A, Frajka-williams E, Josey S A, Evans D G, Grist J P, Marsh R, McCarthy G D, Sinha B, Berry D I and Hirschi J J-M 2015 Drivers of exceptionally cold North Atlantic Ocean temperatures and their link to the 2015 European heat wave Environ. Res. Lett. 11 1–9

Ferrer M and Breteau P 2020 Coronavirus: un pic très net de mortalité en France enregistré en mars et avril Le Monde (available at: www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2020/ 04/27/coronavirus-un-pic-tres-net-de-mortalite-en-france- depuis-le-1er-mars-par-rapport-aux-vingt-dernieres- annees_6037912_4355770.html)

Fischer E M and Knutti R 2015 Anthropogenic contribution to global occurrence of heavy-precipitation and high-temperature extremes Nat. Clim. Change 5 560–4

Frölicher T L, Fischer E M and Gruber N 2018 Marine heatwaves under global warming Nature 560 360–4

Gabbat A and Anguiano D 2023 Hawaii wildfires: deadliest US blaze in a century kills at least 93 people Guard (available at: www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/aug/13/hawaii- wildfires-at-least-89-confirmed-killed-after-deadliest-us- blaze-in-100-years)

Gasparrini A et al 2017 Projections of temperature-related excess mortality under climate change scenarios Lancet Planet. Health 1 e360–7

Hausfather Z 2023 State of the climate: how the world warmed in 2022 Carbon Brief (available at: www.carbonbrief.org/state- of-the-climate-how-the-world-warmed-in-2022/)

Hawkins A 2023 Chinese firefighter ‘dies heroic death’ as Beijing reports heaviest rain in 140 years Guard (available at: www. theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/02/beijing-reports- heaviest-rain-140-years-china-g20-climate-talks)

Himbrechts D 2021 Australia’s Black Summer of fire was not normal—and we can prove it The Conversation (available at: https://theconversation.com/australias-black-summer-of- fire-was-not-normal-and-we-can-prove-it-172506)

Inoue J, Hori M E and Takaya K 2012 The role of Barents Sea ice in the wintertime cyclone track and emergenceof a warm-Arctic cold-Siberian anomaly J. Clim. 25 2561–9

IPCC 2021 Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis.

Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ed V Masson-Delmotte et al (Cambridge University Press) (https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896)

Jain P, Castellanos-Acuna D and Coogan S C P 2022 Observed increases in extreme fire weather driven by atmospheric humidity and temperature Nat. Clim. Chang. 12 63–70

Kornhuber K, Coumou D, Vogel E, Lesk C, Donges J F, Lehmann J and Horton R M 2020 Amplified Rossby waves enhance risk of concurrent heatwaves in major breadbasket regions Nat. Clim. Change 20 48–53

Kretschmer M, Cohen J, Matthias V, Runge J and Coumou D 2018 The different stratospheric influence on cold-extremes in Eurasia and North America npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1 1–10

Luo F et al 2022 Summertime Rossby waves in climate models: substantial biases in surface imprint associated with small biases in upper-level circulation Weather Clim. Dyn.

3 905–35

NASA Earth Observatory 2022 Worst Drought on Record Parches Horn of Africa (available at: https://earthobservatory.nasa. gov/images/150712/worst-drought-on-reco)

Pendergrass A G and Knutti R 2018 The uneven nature of daily precipitation and its change Geophys. Res. Lett.

45 980–11,988

Perkins-Kirkpatrick S E and Lewis S C 2020 Increasing trends in regional heatwaves Nat. Commun. 11 1–8

Rahmstorf S, Box J E, Feulner G, Mann M E, Robinson A, Rutherford S, Scha E J and Schaffernicht E J 2015 Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation Nat. Clim. Change 5 475–80

Robine J M, Cheung S L K, Le Roy S, Van Oyen H, Griffiths C, Michel J P and Herrmann F R 2008 Death toll exceeded 70,000 in Europe during the summer of 2003 C. R. Biol. 331 171–8

Robinson A, Lehmann J, Barriopedro D, Rahmstorf S and Coumou D 2021 Increasing heat and rainfall extremes now far outside the historical climate npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4 3–6

Rousi E, Kornhuber K, Beobide-Arsuaga G, Luo F and Coumou D 2022 Accelerated western European heatwave trends linked to more-persistent double jets over Eurasia Nat. Commun. 13 1–11

Roxy M K, Ghosh S, Pathak A, Athulya R, Mujumdar M, Murtugudde R, Terray P and Rajeevan M 2017 A threefold rise in widespread extreme rain events over central India Nat. Commun. 8 1–11

Senande-Rivera M, Insua-Costa D and Miguez-Macho G 2022 Spatial and temporal expansion of global wildland fire activity in response to climate change Nat. Commun.

13 1–9

Shepherd T G 2014 Atmospheric circulation as a source of uncertainty in climate change projections Nat. Geosci. 7 703–8

Sippel S, Meinshausen N, Fischer E M, Székely E and Knutti R 2020 Climate change now detectable from any single day of weather at global scale Nat. Clim. Change 10 35–41

Touma D, Stevenson S, Lehner F and Coats S 2021 Human-driven greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions cause distinct regional impacts on extreme fire weather Nat. Commun. 12 1–8

USAID 2022 Pakistan Flood Fact Sheet (available at: www.usaid. gov/sites/default/files/2022-12/2022-09- 30_USG_Pakistan_Floods_Fact_Sheet_8.pdf)

Zachariah M, Philip S, Pinto I, Vahlberg M, Singh R, Arrighi J R, Barne C and Otto F E L 2023 Extreme heat in North America, Europe and China in July 2023 made much more likely by climate change (https://doi.org/10.25561/105549)

Zhang R, Sun C, Zhu J, Zhang R and Li W 2020 Increased European heat waves in recent decades in response to shrinking Arctic sea ice and Eurasian snow cover npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3 7

Port Hills is only the beginning

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Last week, wildfire burnt through 650 hectares of forest and scrub in Christchurch’s Port Hills. This is not the first time the area has faced a terrifying wildfire event.

The 2017 Port Hills fires burnt through almost 2,000 hectares of land, claiming one life and 11 homes. It took 66 days before the fires were fully extinguished.

It is clear New Zealand stands at a pivotal juncture. The country faces an increasingly severe wildfire climate. And our once relatively “safe” regions are now under threat.

At all levels of government, New Zealand needs to consider whether our current investment to combat fires will be enough in the coming decades.

Our research integrating detailed climate simulations with daily observations reveals a stark forecast: an uptick in both the frequency and intensity of wildfires, particularly in the inland areas of the South Island.

It is time to consider what this will mean for Fire and Emergency New Zealand (FENZ), and how a strategic calibration of resources, tactics and technologies will help New Zealand confront this emerging threat.

The climate drivers of wildfires

Last year was the warmest year on record by a large margin. And with El Niño at full throttle into 2024, conditions in late-summer Aotearoa New Zealand are hot and dry. There is also plenty of vegetation fuel from the departing wet La Niña.

The tinder-dry scrub and grass vegetation in the Port Hills – an area that was around 30% above “extreme” drought fire danger thresholds – drove the flammability of the region. And on February 13, when the latest fires started, a strong gusty northwesterly wind was blowing 40-50kph with exceptionally dry relative humidity values.

These conditions resulted in the extreme wildfire behaviour. Only the rapid and coordinated response of FENZ on the ground and in the air prevented this fire from becoming much worse.

While conditions are already bad, our study revealed a concerning trend: the widespread emergence of a new wildfire climate, with regions previously unaffected by “very extreme” wildfire conditions now facing unprecedented threats.

The most severe dangers are projected for areas like the Mackenzie Country, upper Otago and Marlborough, where conditions similar to Australia’s “Black Summer” fires could occur every three to 20 years.

This shift is not merely an environmental concern, it is a socioeconomic one. The increased threat of wildfires will affect communities, the government’s tree-planting initiatives and financial investments in carbon forests.

Enhanced resources and agile response

New Zealand’s firefighting strategy emphases speed and manoeuvrability, especially in the initial attack phase, to prevent wildfires from escalating into large-scale disasters.

Approximately NZ$10 million is allocated annually to general firefighting aviation services, translating into around 11,000 flight hours. The aerial battle over the Port Hills peaked on Thursday and Friday. This effort cost over $1 million, with up to 15 helicopters active over the two days.

FENZ operations are primarily funded by property insurance levies. However, with the severity and frequency of wildfires on the rise, it may be necessary to review this funding model to match the evolving risk portfolio.

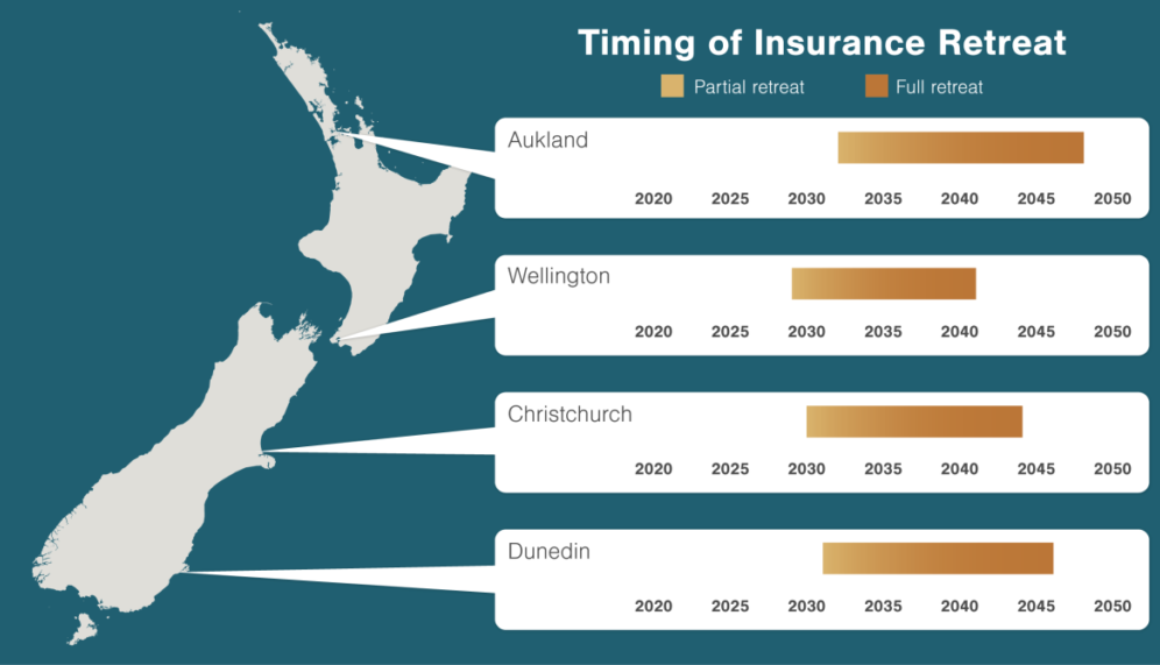

Climate change is already driving insurance retreat – a phenomenon whereby coastal properties are unable to renew their insurance due sea level rise. It is plausible insurance companies could take a similar stance in extremely fire-prone areas.

The agility of FENZ and associated rural fire teams, coupled with the investment and integration of advanced technologies and modelling for better wildfire prediction and management, can significantly enhance the effectiveness of firefighting efforts.

Policy adjustments and community engagement

Adjustments in policy and regulatory frameworks are also crucial in mitigating wildfire risks, and should be explored by experts.

To significantly reduce the ignition of new fires, there needs to be greater implementation of restrictions on access, and banning of high-risk activities, when areas are under “extreme fire risk”.

Moreover, community engagement and preparedness initiatives are vital. One successful example is Mt Iron, Wanaka, where a model was developed after interviews, focus groups and workshops with residents identified wildfire risk awareness and mitigation actions.

Educating vulnerable communities about their wildfire risks and preparedness strategies can also enhance community resilience and safety.

The emergence of a more severe wildfire climate in New Zealand calls for a unified response, integrating increased investment in FENZ, strategic planning and community involvement.

By embracing a multifaceted approach that includes technological innovation, enhanced resource, and community empowerment, New Zealand can navigate the complexities of this new era with resilience and foresight.